FINITE JEST

A radically abridged version of INFINITE JEST

by

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE

Edited for concision by JT THOMAS

Preface

Q. What is FINITE JEST?

A. FINITE JEST is an experiment: a heavily edited, radically condensed version of David Foster Wallace’s novel INFINITE JEST in which every storyline except those related to the Enfield Tennis Academy has been removed. The Enfield Tennis Academy sections were then rearranged to flow in chronological order. No text has been added, only subtracted. The result is a more linear, novella length (100 pp.) reworking of IJ titled The Enfield Tennis Academy, in which Hal Incandenza is the sole protagonist and the world of the novel limited to the tennis academy and its environs. I may or may not make a part two titled The Ennet House along similar lines as part of this project.

Q. Why would you, or anyone, do this?

A. I wanted a reason to engage deeply with the book and figure out why I loved certain sections but found the bulk of it unreadable, even though I have a lot of admiration and affection for the author. I wanted to see if I could actually operationalize my critique of IJ, which is a lot more challenging than just talking trash about it without fully reading the book.

Which is precisely how the novel was treated by my Gen X peers after it was published. For a lot of people who went to college in the 1990s, Wallace’s essays were important and influential, particularly magazine pieces like “David Lynch Keeps His Head” and “Ticket to the Fair”—hilarious, deeply considered critiques that laid bare a lot of contradictions at the heart of American culture. We viewed INFINITE JEST with more suspicion, however. In contrast to the lightness and playful didacticism of the essays, the novel seemed prolix and tonally heavy, written by a sesquepedilian with a bad case of horror vacui and a punny, jejune sense of humor. The imposing doorstopper length (or width) also seemed like a marketing gimmick, but most of us had already bought into the well-established mythology of Wallace as a prodigy and a genius, so we couldn’t be sure. (Our suspicion turned out to be correct: Little, Brown and Company decided that the novel’s excessive length and footnotes would, somewhat counterintuitively, serve as the primary selling point, something for self-regarding readers to brag about. The strategy worked. Over a million copies of IJ now sit dusty and Buddhalike on shelves across America.) None of us had read enough of the novel or could recall enough of it to make a coherent argument, but that didn’t stop anyone from debating its merits at parties and bars and coffeeshops in Iowa City in the late 1990s and 2000s.

Every few years, I would pull IJ off the shelf and give it another shot with varying degrees of success. Without fail, reading the novel gave me a physical headache. I found myself wishing that Michael Pietsch, the editor of IJ who excised hundreds of pages from the novel’s original manuscript, had gone much further (like a Maxwell Perkins-level of further). Some sections of the book seemed to me like white-knuckled exploratory drafts that were more “appended” than integrated, often with characters and plotlines that get introduced but are never developed or returned to. Granted, I wasn’t a connoisseur of the Systems Novel or postmodern metafiction in particular, but graduate school had given me the stubborn and wrongheaded illusion that I could read anything, regardless of how tedious or obscure.

In a 2002 New Yorker essay by Wallace’s friend and contemporary Jonathan Franzen titled “Mr. Difficult: William Gaddis and the Problem of Hard-to-Read-Books,” Franzen makes a distinction between two ways that fiction authors generally relate to their audience. In the Contract Model, a novel represents a compact between the writer and the reader in which the author promises pleasure. Alternately, in the Status Model, novels are works of art by extraordinary minds, and their value exists completely independently of the number of people that appreciate them: if a novel fails to capture a reader’s imagination, that’s their problem. While Franzen’s essay is ostensibly about William Gaddis (another author of inscrutable metafiction who won a MacArthur “Genius Grant” in 1982 when Wallace was an impressionable young undergraduate), in hindsight it reads like a meditation on the need for both the Contract Model novels Franzen was writing like The Corrections, and the Status Model books Wallace was writing like IJ, in a healthy literary ecosystem. Everyone’s a winner!

Franzen’s essay did make me wonder, though, what would IJ have looked like if it had been written as a Contract Model novel? Where would you even start? I thought about something the poet and essayist Mary Karr, also a contemporary of Wallace, said in a 2012 New Yorker panel discussion titled “Rereading David Foster Wallace” that is up on YouTube. Karr recalled her advice to Wallace in the early 1990s after reading drafts of IJ as it was being written, namely that “He should care more about his reader than he did showing off.” I agreed. There was more than a little Lisa Simpson in David Foster Wallace, subtextually shouting “Grade Me!, Grade Me!”

In the same panel discussion, Karr goes on to say, “I think IJ should have been shorter…Most of the stuff in there that I thought was great was non-fiction, was stuff he took from real life.” When I thought about the storylines in the novel that resonated with me, they were indeed the autobiographical sections, particularly the parts of the novel set at the Enfield Tennis Academy and the Ennet House. The characters in these sections seemed to have a lot of subcutaneous connective tissue that was lacking elsewhere. In a piece for the New Yorker titled Did “IJ” Start Out as an Autobiography? that was published in the run up to the 2012 panel discussion, Wallace’s biographer D.T. Max, who went through the archive of Wallace’s papers at the University of Texas that includes the IJ materials, points out the clear distinction between the autofiction sections of the book that reflect Wallace’s experiences as a junior tennis player and an addict in recovery, and the completely fictional elements of the plot that center around a Quebecois Separatist movement—what Michael Pietsch referred to somewhat pejoratively as the “the interAmerican huggermugger.” The international thriller and futurist plotlines in IJ were funny but generally unsatisfying to me as political intrigue or as science fiction…tasty, but undercooked. This is why I decided to follow another major piece of advice Mary Karr gave to Wallace as he was writing IJ: “Cut that Quebecois shit.”

Q. How was “FINITE JEST” edited and condensed?

A. I knew that the text would have to be radically shorter, but what is a reasonable amount of time to ask people to set aside for a single story? I decided to limit the length to 100 pages and one footnote, so that novella could be read in a couple of sessions over a few days. I chose the storyline in the novel that had the most resonance with me, Hal Incandenza’s senior year at the Enfield Tennis Academy and subsequent meltdown, which seemed to be one of the most clearly felt sections of the book and had a full story arc with an emotionally complex cast of characters who shared a deep background. In a way, the Incandenza family reminded me of Salinger’s Glass family, filled with siblings bearing preternatural intelligence or outright genius and adult emotional problems.

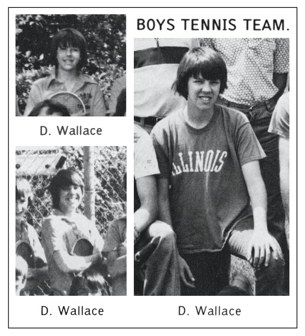

David Foster Wallace, pictured here at around the age of Mario and Hal Incandenza in IJ

In terms of the actual process, I highlighted all of the Enfield Tennis Academy portions from a pdf of the novel, extracted them into a new document, and then rearranged them in chronological order as best as possible (some sections still contain flashbacks, however). The process was reductive and highly subjective. Hundreds of references to characters, events, or storylines from other parts of the novel had to be removed so that the Enfield Tennis Academy narrative made sense and could stand alone as self-contained novella. Some text within short sections has been rearranged for clarity and flow, but I did my best to preserve the original meaning at the sentence level. At less than 10% of the length of the original novel, FINITE JEST is missing the majority of characters and plotlines and thus doesn’t contain most of the larger, open-ended themes in the novel. However, I think point of the book—that everything in our culture has become a drug or a potential addiction—still comes through, even in my truncated version.

There’s obviously a lot more that went into the editorial choices, so if you would like to know more feel free to email me. I’m sure many fans of Wallace would think this experiment is sacrilege. For this reason, I suggest that they not attempt to edit and recut IJ in order to create their own bespoke version of the novel. It is time consuming and without external reward.

*A note on time: In the original novel, the Enfield Tennis Academy sections take place in the “future,” roughly around the year 2009. Within the futurist world of the novel, years are no longer given numbers, and instead named after corporate sponsors. A large part of IJ centers around Hal’s senior year in high school, named the Year of the Depends Adult Undergarment. But because I didn’t retain the other chapter titles, which are similarly named for products, referring to the Year of the Depends Adult Undergarment or “YDAU” didn’t make much sense. Although Wallace was extraordinarily prescient about the effect of the modern world on our psyches, but he was not a talented futurist in a technological sense. The world of the Enfield Tennis Academy resembles the era in which Wallace came of age, between the late 1970s and early 1990s. Information is still disseminated in books and entertainment cartridges similar to VHS or Betamax tapes. The internet is mentioned in passing, but plays no significant role. Wallace doesn’t anticipate our ubiquitous adoption of cell phones, just around the corner, nor social media, AI, or any of the major technological innovations that came to define life the early 21st century. For this reason, I set FINITE JEST at the time Wallace was writing it, around 1992, which seems about right in terms of the material culture discussed in the novel.

****

The following is a substantially transformative work of literary criticism, protected under the U.S. fair use doctrine, a legal principle that permits the unlicensed use of copyright-protected materials for certain purposes, such as criticism, commentary, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research.

****

The Enfield Tennis Academy

MONDAY NOV 2 1992

Here’s Hal Incandenza, age seventeen, with his little brass one-hitter, getting covertly high in the Enfield Tennis Academy’s underground Pump Room and exhaling palely into an industrial exhaust fan. It’s the sad little interval after afternoon matches and conditioning but before the Academy’s communal supper. Hal is by himself down here and nobody knows where he is or what he’s doing.

Hal likes to get high in secret, but a bigger secret is that he’s as attached to the secrecy as he is to getting high.

A one-hitter, sort of like a long FDR-type cigarette holder whose end is packed with a pinch of dope, gets hot and is hard on the mouth—the brass ones especially—but one-hitters have the advantage of efficiency: every particle of ignited pot gets inhaled; there’s none of the incidental secondhand-type smoke from a party bowl’s load, and Hal can take every iota way down deep and hold his breath forever, so that even his exhalations are no more than slightly pale and sick-sweet-smelling.

Total utilization of available resources = lack of publicly detectable waste.

The Academy’s tennis courts’ Lung’s Pump Room is underground and accessible only by tunnel. E.T.A. is abundantly, embranchingly tunnelled. This is by design. Plus one-hitters are small, which is good, because let’s face it, anything you use to smoke high-resin dope with is going to stink. A bong is big, and its stink is going to be like commensurately big, plus you have the foul bong-water to deal with. Pipes are smaller and at least portable, but they always come with only a multi-hit party bowl that disperses nonutilized smoke over a wide area. A one-hitter can be wastelessly employed, then allowed to cool, wrapped in two baggies and then further wrapped and sealed in a Ziploc and then enclosed in two sport-socks in a gear bag along with the lighter and eyedrops and mint-pellets and the little film-case of dope itself, and it’s highly portable and odor-free and basically totally covert.

As far as Hal knows, colleagues Michael Pemulis, Jim Struck, Bridget C. Boone, Jim Troeltsch, Ted Schacht, Trevor Axford, and possibly Kyle D. Coyle and Tall Paul Shaw, and remotely possibly Frannie Unwin, all know Hal gets regularly covertly high. And Hal’s brother Mario knows a thing or two. But that’s it, in terms of public knowledge. And but even though Pemulis and Struck and Boone and Troeltsch and Axford and occasionally (in a sort of medicinal or touristic way) Slice and Schacht all are known to get high also, Hal has actually gotten actively high only with Pemulis, on the rare occasions he’s gotten high with anybody else, as in in person, which he avoids. He’d forgot: Hal’s oldest brother, Orin, mysteriously, even long-distance, seems to know more than he’s coming right out and saying, unless Hal’s reading more into some of the phone-comments than are there.

Hal’s mother, Mrs. Avril Incandenza, and her adoptive brother Dr. Charles Tavis, the current E.T.A. Headmaster, both know Hal drinks alcohol sometimes, like on weekend nights with Troeltsch or maybe Axford down the hill at clubs on Commonwealth Ave.; The Unexamined Life has its notorious Blind Bouncer night every Friday where they card you on the Honor System. Mrs. Avril Incandenza isn’t crazy about the idea of Hal drinking, mostly because of the way his father James Incandenza Himself had drunk, when alive, and reportedly his father’s own father before him; but Hal’s academic precocity, and especially his late competitive success on the junior circuit, make it clear that he’s able to handle whatever modest amounts she’s pretty sure he consumes — there’s no way someone can seriously abuse a substance and perform at top scholarly and athletic levels, the E.T.A. psych- counselor Dr. Rusk assures her, especially the high-level-athletic part—and Avril feels it’s important that a concerned but un-smothering single parent know when to let go somewhat and let the two high-functioning of her three sons make their own possible mistakes and learn from their own valid experience, no matter how much the secret worry about mistakes tears her gizzard out. And Charles supports whatever personal decisions she makes in conscience about her children. And God knows she’d rather have Hal having a few glasses of beer every so often than absorbing God alone knows what sort of esoteric designer compounds with reptilian Michael Pemulis and trail-of-slime-leaving James Struck, both of whom give Avril a howling case of the maternal fantods. And ultimately, she’s told Drs. Rusk and Tavis, she’d rather have Hal abide in the security of the knowledge that his mother trusts him, that she’s trusting and supportive and doesn’t judge or gizzard-tear or wring her fine hands over his having for instance a glass of Canadian ale with friends every now and again, and so works tremendously hard to hide her maternal dread of his possibly ever drinking like his father or James’s father, all so that Hal might enjoy the security of feeling that he can be up-front with her about issues like drinking and not feel he has to hide anything from her under any circumstances.

Dr. Tavis and Dolores Rusk have privately discussed the fact that not least among the phobic stressors Avril suffers so uncomplainingly with is a black phobic dread of hiding or secrecy in all possible forms with respect to her sons.

Avril and C.T. know nothing about Hal’s penchants for high-resin Bob Hope and underground absorption, which Hal obviously likes a lot, on some level, though he’s never given much thought to why.

E.T.A.’s hilltop grounds are traversable by tunnel. Avril I., for example, who never leaves the grounds anymore, rarely travels above ground, willing to hunch to take the off-tunnels between Headmaster’s House and her office next to Charles Tavis’s in the Community and Administration Bldg., a pink-bricked white-pillared neo-Georgian thing that Hal’s brother Mario says looks like a cube that has swallowed a ball too big for its stomach. One large tunnel of elephant-colored cement leads from just off the boys’ showers to the mammoth laundry room below the West Courts, and two smaller tunnels radiate from the sauna area south and east to the subbasements of the smaller, spherocubular, proto-Georgian buildings (housing classrooms and subdormitories B and D). Then two even smaller tunnels are in turn connected to E.T.A.’s Lung-Storage and Pump Rooms via a pargeted tunnel hastily constructed by the TesTar All-Weather Inflatable Structures Corp., which erects and services the inflatable dendriurethane dome, known as the Lung, that covers the middle row of courts for the winter indoor season. The crude little rough-sided tunnel between Plant and Pump is traversable only via all-fours-type crawling and is essentially unknown to staff and Administration, popular only with the Academy’s smaller kids’ Tunnel Club, as well as with certain adolescents with strong secret incentive to crawl on all fours.

The Lung-Storage Room is basically impassable from March through November because it’s full of intricately folded and dismantled sections of flexible ducting and fan-blades, etc. When the courts’ Lung is down and stored, Hal will descend and walk and then hunch his way in to make sure nobody’s in the Physical Plant quarters, then he’ll hunch and crawl to the P.R., gear bag in his teeth, and activate just one of the big exhaust fans and get secretly high and exhale palely through its blades into the vent, so that any possible odor is blown through an outtake duct and expelled through a grille’d hole on the west side of the West Courts.

During winter months, when any expelled odor would get ducted up into the Lung and hang there conspicuous, Hal mostly goes into a remote sub-dormitory lavatory and climbs onto a toilet in a stall and exhales into the grille of one of the little exhaust fans in the ceiling; but this routine lacks a certain intricate subterranean covert drama. It’s another reason why Hal dreads the approach of the WhataBurger Classic and Thanksgiving and unendurable weather, and the erection of the Lung.

Recreational drugs are more or less traditional at any U.S. secondary school, maybe because of the unprecedented tensions: post-latency and puberty and angst and impending adulthood, etc. To help manage the intra-psychic storms, etc. Since the place’s inception, there’s always been a certain percentage of the high-caliber adolescent players at E.T.A. who manage their internal weathers chemically. Much of this is good clean temporary fun; but a traditionally smaller and harder-core set tends to rely on personal chemistry to manage E.T.A.’s special demands—dexedrine or low-volt methedrine before matches and benzodiazapenes to come back down after matches, with Mudslides or Blue Flames at some understanding Comm. Ave. nightspot or beers and bongs in some discreet Academy corner at night to short-circuit the up-and-down cycle, mushrooms or X or something from the Mild Designer class—or maybe occasionally a little Black Star, whenever there’s a match- and demand-free weekend, to basically short out the whole motherboard and blow out all the circuits and slowly recover and be almost neurologically reborn and start the gradual cycle all over again…this circular routine, if your basic wiring’s OK to begin with, can work surprisingly well throughout adolescence and sometimes into one’s like early twenties, before it starts to creep up on you.

But so some E.T.A.s—not just Hal Incandenza by any means—are involved with recreational substances, is the point. Like who isn’t, at some life-stage, in the U.S.A., in these troubled times, for the most part. American experience seems to suggest that people are virtually unlimited in their need to give themselves away, on various levels. Some just prefer to do it in secret.

An enrolled student-athlete’s use of alcohol or illicit chemicals is cause for immediate expulsion, according to E.T.A.’s admissions catalogue. But the E.T.A. staff tends to have a lot more important stuff on its plate than policing kids who’ve already given themselves away to an ambitious competitive pursuit. The administrative attitude under first James Incandenza and then Charles Tavis is, like, why would anybody who wanted to compromise his faculties chemically even come here, to E.T.A., where the whole point is to stress and stretch your faculties along multiple vectors. And since it’s the alumni prorectors who have the most direct supervisory contact with the kids, and since most of the prorectors themselves are depressed or traumatized about not making it into the Show and having to come back to E.T.A. and live in decent but subterranean rooms off the tunnels and work as assistant coaches and teach laughable elective classes—which is what the eight E.T.A. prorectors do, when they’re not off playing Satellite tournaments or trying to make it through the qualifying rounds of some serious-money event— and so they’re morose and low on morale, and feel brfad about themselves, often, as a rule, and so also not all that surprisingly tend to get high now and then themselves, though in a less covert or exuberant fashion than the hard-core students’ chemical cadre, but so given all this it’s not hard to see why internal drug-enforcement at E.T.A. tends to be flaccid.

The other nice thing about the Pump Room is the way it’s connected by tunnel to the prorectors’ rows of housing units, which means men’s rooms, which means Hal can crawl, hunch, and tiptoe into an unoccupied men’s room and brush his teeth with his Oral-B and wash his face and apply eyedrops and Old Spice and a plug of wintergreen Kodiak and then saunter back to the sauna area and ascend to ground level looking and smelling right as rain, because when he gets high he develops a powerful obsession with having nobody — not even the neurochemical cadre—know he’s high. This obsession is almost irresistible in its force. The amount of organization and toiletry-lugging he has to do to get secretly high in front of a subterranean outtake vent in the pre-supper gap would make a lesser man quail. Hal has no idea why this is, or whence, this obsession with the secrecy of it. He broods on it abstractly sometimes, when high: this No-One-Must-Know thing. It’s not fear per se, fear of discovery. Beyond that it all gets too abstract and twined up to lead to anything, Hal’s brooding. Like most North Americans of his generation, Hal tends to know way less about why he feels certain ways about the objects and pursuits he’s devoted to than he does about the objects and pursuits themselves. It’s hard to say for sure whether this is even exceptionally bad, this tendency.

NOV 1992

EARLY MORNING

Another way fathers impact sons is that sons, once their voices have changed in puberty, invariably answer the telephone with the same locutions and intonations as their fathers. This holds true regardless of whether the fathers are still alive.

Because he left his dormitory room before 0600 for dawn drills and often didn’t get back there until after supper, packing his book bag and knapsack and gear bag for the whole day, together with selecting his best-strung racquets—it all took Hal some time. Plus he usually collected and packed and selected in the dark, and with stealth, because his brother Mario was usually still asleep in the other bed. Mario didn’t drill and couldn’t play, and needed all the sleep he could get.

Hal held his complimentary gear bag and was putting different pairs of sweats to his face, trying to find the cleanest pair by smell, when the phone sounded. Mario thrashed and sat up in bed, a small hunched shape with a big head against the gray light of the window. Hal got to the phone on the second ring.

His way of answering the phone sounded like ‘Mmmyellow.’

‘I want to tell you,’ the voice on the phone said. ‘My head is filled with things to say.’

Hal held three pairs of E.T.A. sweatpants in the hand that didn’t hold the phone. He saw his older brother succumb to gravity and fall back limp against the pillows. Mario often sat up and fell back still asleep.

‘I don’t mind,’ Hal said softly. ‘I could wait forever.’

‘That’s what you think,’ the voice said. The connection was cut. The person on the phone had been Orin.

‘Hey Hal?’

The light in the room was a creepy gray, a kind of nonlight. Hal could hear the clank of janitorial buckets down the hall.

‘Hey Hal?’ Mario was awake. It took four pillows to support Mario’s oversized skull. His voice came from the tangled bedding. ‘Is it still dark out, or is it me?’

‘Go back to sleep. It isn’t even six.’ Hal put the good leg into the sweatpants first.

‘Who was it?’

Shoving three coverless Dunlop widebodies into the gear bag and zipping the bag partway up so the handles had room to stick out he said, ‘No one you know, I don’t think.’

MONDAY NOV 9 1992

ETA PLAY

The Enfield Tennis Academy has an accredited capacity of 148 junior players—of whom 80 are to be male—but an actual population of 136, of which 72 are female. Charles Tavis and Co. are wanting to fill all twelve available spots with males—they wouldn’t exactly mind, is the general scuttlebutt, if a half dozen or so of the better girls left before graduation and tried for the Show, simply because housing more girls means putting some in the male dorms, which creates tensions and licensing- and conservative-parent-problems, given that coed hall bathrooms are not a good idea what with all the adolescent glands firing all over the place. A.M. drills have to be complexly staggered, the boys in two sets of 32, the girls in three of 24.

Matriculations, gender quotas, recruiting, financial aid, room-assignments, mealtimes, rankings, class v. drill schedules, prorector-hiring, accommodating changes in drill schedule consequent to a player’s movement up or down a squad. It’s all the sort of thing that’s uninteresting unless you’re the one responsible, in which case it’s cholesterol-raisingly stressful and complex. The stress of all the complexities and priorities to be triaged and then weighted against one another gets Charles Tavis out of bed in the Headmaster’s House at an ungodly hour most mornings, his sleep-swollen face twitching with permutations. He stands in leather slippers at the living-room window, looking southeast past West and Center Courts at the array of A-team players assembling stiffly in the gray glow, carrying gear with their heads down and some still asleep on their feet, the first bit sun protruding through the city’s little skyline far beyond them, Tavis’s hands working nervously around the cup of hazlenut decaf that steams upward into his face, forehead up against the window’s glass so he can feel the mean chill of the dawn just outside. The A-team’s array keeps shifting and melding as they await Schtitt.

Tavis watches the boys stretch and confer and sips from the cup with both hands, the concerns of the day assembling themselves in a sort of tree-diagram of worry. Charles Tavis knows what James Incandenza could not have cared about less: the key to the successful administration of a top-level junior tennis academy lies in cultivating a kind of reverse-Buddhism, a state of Total Worry. So the best E.T.A. players’ special perk is they get hauled out of bed at dawn, still crusty-eyed and pale with sleep, to drill in the first shift.

Dawn drills are of course alfresco until they erect and inflate the Lung, which Hal Incandenza hopes is soon. His circulation is poor because of tobacco and/or marijuana, and even with his DUNLOP-down-both-legs sweatpants and a turtleneck and thick old white alpaca tennis jacket that had been his father’s and has to be rolled up at the sleeves, he’s sullen and chilled, and by the time they’ve run the pre-stretch sprints up and down the E.T.A. hill four times, swinging their sticks madly in all directions and making various half-hearted warrior-noises, Hal is both chilled and wet, and his sneakers squelch from dew as he hops in place and looks at this breath, wincing as the cold air hits the one bad tooth.

By the time they’re all stretching out, lined up in rows, flexing and bowing, genuflecting to nothing, changing postures at the sound of a whistle, the sky has lightened to the color of Kaopectate. All the lesser players are still abed. Hal’s breath hangs before his face until he moves through it. Sprints produce the sick sound of much squelching; everyone wishes the hill’s grass would die.

Twenty-four girls are drilled in groups of six on four of the Center Courts. The 32 boys are split by rough age into fours and take a semi-staggered eight of the East Courts. Schtitt is up in his little observational crow’s nest, a sort of apse at the end of the iron transom players call the Tower that extends west to east over the centers of all three sets of courts and terminates w/ the nest high

above the courts. He has a chair and an ashtray up there. Sometimes from the courts you can see him leaning over the railing, tapping the edge of the bullhorn with his weatherman’s pointer; from the West and Center Courts the rising sun behind him gives his white head a pinkish corona.

Except during periods of disciplinary conditioning, alfresco A.M. drills work like this. A prorector is at each relevant court with two yellow Ball-Hopper-brand baskets of used balls, plus a ball machine, which machine looks like an open footlocker with a blunt muzzle at one end pointed across the net at a quartet of boys. Hal hops up and down in his capacious jacket and plum turtleneck and looks at his breath and tries to focus very intently on the pain of his tooth without judging it as bad or good.

Each quartet starts at a different court and rotates around. Corbett Thorp lays down squares of electrician’s tape at the court’s corners and they are strongly encouraged to hit the balls into the little squares. Hal hits with Stice, Coyle with Wayne. Hal’s tooth hurts and his ankle is stiff and the cold balls come off his strings with a dead sound like chung. Tiny bratwursts of smoke ascend rhythmically from Schtitt’s little nest. Hal and Coyle, both sucking wind after twenty and trying to stand up straight, feed lobs to Wayne and Stice, neither of whom is fatiguable as far as anyone can tell. Overhead, Schtitt uses an unamplified bullhorn and careful enunciation to call out for everyone to hear that Mr. revenant Hal Incandenza was letting the ball get behind him on over-heads, fears of the ankle maybe. To hang in past age fourteen here is to become immune to humiliation from staff. Coyle tells Hal between the lobs they send up he’d love to see Schtitt have to do twenty Tap & Whacks in a row. They’re all flushed to a shine, all chill washed off, noses running freely and heads squeaking with blood. The watching prorectors stand easy with their legs apart and their arms crossed over their racquets’ faces. The same three or four booger-shaped clouds seem to pass back and forth overhead, and when they cover the sun people’s breath reappears. Stice blows on his racquet-hand and cries out thinly for the inflation of the Lung. Mr. A.F. deLint ranges behind the fence with his clipboard and whistle, blowing his nose. The girls behind him are bundled up, their hair rubber-banded into little bouncing tails.

Then, blessedly, physically undemanding Finesse drills. Drops, drops for angles, topspin lobs, extreme angles, drops for extreme angles. Touch- and artistry-wise nobody comes close to Hal. By this time Hal’s turtleneck is soaked through under the alpaca jacket, and exchanging it for a sweatshirt out of the gear bag is a kind of renewal. What wind there is down here is out of the south. The temperature is now probably in the low 10’s C.; the sun’s been up an hour. The sky is going a glassy blue.

No (tennis) balls required on the final court. Wind sprints. Probably the less said about wind sprints the better. Then more Gatorade, which Hal and Coyle are breathing too hard to enjoy, as Schtitt comes slowly down from the transom. It takes a while. You can hear his steel-toed boots hit each iron step. There is something creepy about a very fit older man, to say nothing of jackboots w/ Fila warm-ups of claret-colored silk. Schtitt’s crew cut and face are nacreous as he moves east in the yellowing A.M. light. This is sort of the signal for all the quartets to gather at the Show Courts.

Coyle — he of the weak bladder and suspicious discharge—gets excused to go back into the eastern tree-line and pee, so the other three get a minute to jog over to the pavilion and stand with their hands on their hips and breathe and drink Gatorade out of little conic paper cups you can’t put down til they’re empty. Schtitt stands at a sort of Parade Rest with his weatherman’s pointer behind his back and shares overall impressions with the players on the morning’s work thus far. Certain players are singled out for special mention or humiliation. Then more wind sprints.

Schtitt has a stopwatch. There’s a janitorial bucket placed in the doubles alley by the finish point, for potential distress.

The cardiovascular finale is Side-to-Sides, demonic in its simplicity. What’s potentially demonic about Side-to-Sides is that the duration of the drill and pace and angle of the fungoes to be chased down from side to side are entirely at the prorector’s discretion. A very unpleasant drill fatigue-wise, and for Hal also ankle-wise, what with all the stopping and reversing. Hal wears two bandages over a left ankle he shaves way more often than his upper lip. Over the bandages goes an Air-Stirrup inflatable ankle brace that’s very lightweight but looks a bit like a medieval torture-implement. It was in a stop-and-reverse move much like Side- to-Sides that Hal tore all the soft left-ankle tissue he then owned at fifteen, at Atlanta’s Easter Bowl, in the third round, which he was losing anyway. Dunkel goes fairly easy on Hal, at least on the first two go-arounds, because of the ankle. Hal’s going to be seeded in at least the top 4 at the WhataBurger Inv. in a couple weeks, and woe to the prorector who lets Hal get hurt.

It is O72Oh. and they are through with the active part of dawn drills. Schtitt shares more overall impressions as minimum-wage aides dispense Kleenex and paper cones, pacing back and forth with about-faces at every tenth step, stopwatch around his neck, pipe and pouch and pointer in his hands behind his back, nodding to himself, clearly wishing he had a third hand so he could stroke his white chin, pretending to ruminate. All the older boys’ eyes are glazed with repetition. Hal’s tooth gives off little electric shivers with each inbreath, and he feels slightly unwell. When he moves his head slightly the monitor-glass bits’ glitter shifts and dances along the opposite fence in a sort of sickening way.

‘Put a lid on it about the fucking cold,’ says deLint, with his clipboard under his arm and his strangler-sized hands in his pockets, hopping a little in place. Schtitt is looking around. Like most Germans outside popular entertainment, he gets quieter when he wants to impress or menace. (There are very few shrill Germans, actually.) ‘It can be arranged for you gentlemen not to leave, ever, this world inside the lines of court. You can stay right here.’ The pointer is pointed at the spots they’re standing at breathing and blotting their faces and blowing their noses. ‘Sleep bags. Meals brought to you. Never across the lines. Never leave the court. Study here. A bucket for hygienic needs. At Gymnasium Kaiserslautern where I am privileged boy whining about cold wind, we live inside tennis court for months. Very lucky days when they bring us meals.’

Hal very subtly shoots in a small plug of Kodiak. Aubrey deLint has his arms crossed over the clipboard and is looking around beadily like a crow. Hal Incandenza has an almost obsessive dislike for deLint, whom he tells Mario he sometimes cannot quite believe is even real, and tries to get to the side of, to see whether deLint has a true z coordinate or is just a cutout or projection. The kids of the next shift are walking downhill and sprinting back up and walking down, warrior-whooping without conviction. The other male prorectors are drinking cones of Gatorade, clustered in the little pavilion, feet up on patio-chairs.

‘Simple,’ Schtitt shrugs, so that the upraised pointer seems to stab at the sky. ‘Hit,’ he suggests. ‘Move. Travel lightly. Occur. Be here. Not in bed or shower or over baconschteam, in the mind. Be here in total. Nothing else. Learn. Try. Drink your green juice. Perform the Butterfly exercises on all eight of these courts, please, to warm down. Gentlemen: hit tennis balls. Fire at will.’

Schtitt sweeps the pointer in an ironic morendo arc and laughs aloud:

‘Play.’

OCTOBER 1992

Four times per annum, in these chemically troubled times, the Organization of North American Nations Tennis Association’s Juniors Division sends a young toxicologist with cornsilk hair and a smooth wide button of a nose and a blue O.N.A.N.T.A. blazer to collect urine samples from any student at any accredited tennis academy ranked higher than #64 continentally in his or her age-division. Competitive junior tennis is meant to be good clean fun. It’s October. An impressive percentage of the kids at E.T.A. are in their divisions’ top 64. On urine-sample day, the juniors form two long lines that trail out of the locker rooms and up the stairs and then run agnate and coed across the E.T.A. Comm.-Ad. Bldg. lobby with its royal-blue shag and hardwood panelling and great glass cases of trophies and plaques. It takes about an hour to get from the middle of the line to your locker room’s stall-area, where either the blond young toxicologist or on the girls’ side a nurse whose severe widow’s peak tops her square face with a sort of bisected forehead dispenses a plastic cup with a pale-green lid and a strip of white medical tape with a name and a monthly ranking and 10-15-1992 and Enf.T.A. neatly printed in a six-pt. font.

Probably about a fourth of the ranking players over, say, fifteen at the Enfield Tennis Academy cannot pass a standard North American GC/MS urine scan. These, seventeen-year-old Michael Pemulis’s nighttime customers, now become also, four times yearly, his daytime customers. Clean urine is ten dollars a cc.

‘Get your urine here!’ Pemulis and Trevor Axford become quarterly urine vendors; they wear those papery oval caps ballpark-vendors wear; they spend three months collecting and stashing the urine of sub-ten-year-old players, warm pale innocent childish urine that’s produced in needly little streams and the only G/M scan it couldn’t pass would be like an Ovaltine scan or something; then every third month Pemulis and Axford work the agnate unsupervised line that snakes across the blue lobby shag, selling little Visine bottles of urine out of an antique vendor’s tub for ballpark wieners, a big old box of dull dimpled tin with a strap in Sox colors that goes around the back of the neck and keeps the vendor’s hands free to make change.

‘Urine!’

‘Clinically sterile urine!’

‘Piping hot!’

‘Urine you’d be proud to take home and introduce to the folks!’

Trevor Axford handles cash-flow. Pemulis dispenses little conical-tipped Visine bottles of juvenile urine, bottles easily rendered discreet in underarm, sock or panty.

‘Urine trouble? Urine luck!’

Quarterly sales breakdowns indicate slightly more male customers than female customers for urine. Tomorrow morning, E.T.A. custodial workers—sullen and shifty-eyed residents from Ennet House, the halfway facility at the bottom of the hill in the old VA Hospital complex, hard-looking and generally sullen types who come and do nine months of menial-type work for the 32 hours a week their treatment-contract requires—will empty scores of little empty plastic Visine bottles from subdorm wastebaskets into the dumpster-nest behind the E.T.A. Employee parking lot, from which dumpsters Pemulis will then get Mario Incandenza and some of the naïver of the original ephebic urine-donators themselves to remove, sterilize, and rebox the bottles under the guise of a rousing game of Who-Can-Find,-Boil,-And-Box-The-Most-Empty-Visine-Bottles-In-A-Three-Hour-Period-Without-Any-Kind-Of-Authority-Figure-Knowing-What-You’re-Up-To, a game which Mario had found thumpingly weird when Pemulis introduced him to it three years

ago, but which Mario’s really come to look forward to, since he’s found he has a real sort of mystical intuitive knack for finding Visine bottles in the sedimentary layers of packed dumpsters, and always seems to win hands-down, and if you’re poor old Mario Incandenza you take your competitive strokes where you can find them.

Hal’s older brother Mario—who by Dean of Students’ fiat gets to bunk in a double with Hal in subdorm A on the third floor of Comm.-Ad. even though he’s too physically challenged even to play low-level recreational tennis, but who’s keenly interested in video- and film production, and pulls his weight as part of the E.T.A. community recording assigned sections of matches and drills and processional stroke-filming sessions for later playback and analysis by Schtitt and his staff—is filming the congregated line and social interactions and vending operation of the urine-day lobby, apparently getting footage for one of the short strange Himself-influenced conceptual films the administration lets him occupy his time making and futzing around with down in the late founder’s editing and f/x facilities off the main sub-Comm.-Ad. Tunnel.

They do brisk business.

Michael Pemulis, wiry, pointy-featured, phenomenally talented at net but about two steps too slow to get up there effectively against high-level pace—so in compensation also a great offensive-lob man—is a scholarship student from right nearby in Allston MA—a grim section of tract housing and vacant lots, low-rise Greek and Irish housing projects, gravel and haphazard sewage and indifferent municipal upkeep—an Inner City Development Program tennis prodigy at ten, recruited up the hill at eleven. Cavalier about practice but a bundle of strangled nerves in tournaments, the rap on Pemulis is that he’s way lower-ranked than he could be with a little hard work. Pemulis, whose pre-E.T.A. home life was apparently hackle-raising, also sells small-time drugs of distinguished potency at reasonable retail prices to a large pie-slice of the total junior-tournament-circuit market. Mario Incandenza is one of those people who wouldn’t see the point of trying recreational chemicals even if he knew how to go about it. He just wouldn’t get it. His smile, below the Bolex camera strapped to his large but sort of withered-looking head, is constant and broad as he films the line’s serpentine movement against glass shelves full of prizes.

M.M. Pemulis, whose middle name is Mathew (sic), has the highest Stanford-Bïnet of any kid on academic probation ever at the Academy. Hal Incandenza’s most valiant efforts barely get Pemulis through Mrs. I’s triad of required Grammars (Prescriptive Grammar, Descriptive Grammar, Grammar and Meaning) and Soma R.-L.-O. Chawaf’s heady Literature of Discipline, because Pemulis, who claims he sees every third word upside-down, actually just has a born tech-science wienie’s congenital impatience with the referential murkiness and inelegance of verbal systems. His early tennis promise quick-peaking and it’s turned out a bit dilettantish, Pemulis’s real enduring gift is for math and hard science, and his scholarship is the coveted James O. Incandenza Geometrical Optics Scholarship, of which there is only one, and which each term Pemulis manages to avoid losing by just one dento-dermal layer of overall G.P.A., and which gives him sanctioned access to all the late director’s lenses and equipment, some of which turn out to be useful to unrelated enterprises. Mario’s the only other person sharing the optic-and-editing labs off the main tunnel, and the two have the kind of transpersonal bond that shared interests and mutual advantage can inspire. Mario and his brother Hal both consider Pemulis a good friend, though friendship at E.T.A. is nonnegotiable currency.

Hal Incandenza for a long time identified himself as a lexical prodigy who—though Avril had taken pains to let all three of her children know that her nonjudgmental love and pride depended in no way on achievement or performance or potential talent—had made his mother proud, plus a really good tennis player. Hal Incandenza is now being encouraged to identify himself as a late-blooming prodigy and possible genius at tennis who is on the verge of making every authority-figure in his world and beyond very proud indeed. He’s never looked better on court or on monthly O.N.A.N.T.A. paper. He is erumpent. He has made what Schtitt termed a ‘leap of exponents’ at a post-pubescent age when radical, plateaux-hopping, near-Show-caliber improvement is extraordinarily rare in tennis. He gets his sterile urine gratis, though he could well afford to pay: Pemulis depends on him for verbal-academic support, and dislikes owing favors, even to friends.

Hal is, at seventeen, judged ex cathedra the fourth-best tennis player under age eighteen in the United States of America, and the sixth-best on the continent, by those athletic-organizing bodies duly charged with the task of ranking. Hal’s head, closely monitored by deLint and Staff, is judged still level and focused and unswollen/-bludgeoned by the sudden éclat and rise in general expectations. When asked how he’s doing with it all, Hal says Fine and thanks you for asking.

If Hal fulfills this newly emergent level of promise and makes it all the way up to the Show, Mario will be the only one of the Incandenza children not wildly successful as a professional athlete. No one who knows Mario could imagine that this fact would ever even occur to him.

Orin, Mario, and Hal’s late father was revered as a genius in his original profession without anybody ever realizing what he really turned out to be a genius at, even he Himself, at least not while he was alive, which is perhaps bona-fidely tragic but also, as far as Mario’s concerned, ultimately all right, if that’s the way things unfolded.

Certain people find people like Mario Incandenza irritating or even think they’re outright dead inside in some essential way.

Michael Pemulis’s basic posture with people is that Mrs. Pemulis raised no dewy-eyed fools. He wears painter’s caps on-court and sometimes a yachting cap turned around 180°, and, since he’s not ranked high enough to get any free-corporate-clothing offers, plays in T-shirts with things like ALLSTON HS WOLF SPIDERS and CHOOSY MOTHERS and THE FIENDS IN HUMAN SHAPE TOUR or like an ancient CAN YOU BELIEVE IT THE SUPREME COURT JUST DESECRATED OUR FLAG on them. His face is the sort of spiky-featured brow-dominated Feen-ian face you see all over Irish Allston and Brighton, its chin and nose sharp and skin the natal brown color of the shell of a quality nut.

Michael Pemulis is nobody’s fool, and he fears the dealer’s Brutus, the potential eater of cheese, the rat, the wiretap, the pubescent-looking Finest sent to make him look foolish. So when somebody calls his room’s phone and wants to buy some sort of substance, they have to right off the bat utter the words ‘Please commit a crime,’ and Michael Pemulis will reply ‘Gracious me and mine, a crime you say?’ and the customer has to insist, right over the phone, and say he’ll pay Michael Pemulis money to commit a crime, or like that he’ll harm Michael Pemulis in some way if he refuses to commit a crime, and Michael Pemulis will in a clear and I.D.able voice make an appointment to see the caller in person to ‘plead for my honor and personal safety,’ so that if anybody eats cheese later or the phone’s frequency is covertly accessed, somehow, Pemulis will have been entrapped.

Secreting a small Visine bottle of urine in an armpit in line also brings it up to plausible temperature. At the entrance to the male stall-area, the ephebic-looking O.N.A.N.T.A. toxicologist rarely even looks up from his clipboard, but the square-faced nurse can be a problem over on the female side, because every so often she’ll want the stall door open during production. Pemulis also offers, at reasonable cost, a small vade mecumish pamphlet detailing several methods for dealing with this contingency.

1987

James Orin Incandenza—the only child of a former top U.S. jr. tennis player, a father who somewhere around the nadir of his professional fortunes apparently decided to go down to his Raid-sprayed basement workshop and build a promising junior athlete the way other fathers might restore vintage autos or build ships inside bottles, or like refinish chairs, etc. — James Incandenza proved a withdrawn but compliant student of the game and soon a gifted jr. player who used tennis scholarships to finance, on his own, private secondary and then higher education at places just about as far away from the U.S. Southwest as one could get without drowning. The United States government’s prestigious O.N.R. (Office of Naval Research, U.S.D.D.) financed his doctorate in optical physics, fulfilling something of a childhood dream. His strategic value as more or less the top applied-geometrical-optics man in the O.N.R. designing neutron-scattering reflectors for thermo-strategic weapons systems, then in the Atomic Energy Commission, translated, after an early retirement from the public sector, into a patented fortune in rearview mirrors, light-sensitive eyewear, holographic birthday and Xmas greeting cards, videophonic Tableaux, homolosine-cartography software, nonfluorescent public-lighting systems and film-equipment; then the opening a U.S.T.A.-accredited and pedagogically experimental tennis academy, and conceptual-film work too far either ahead of or behind its time—although a lot of it was admittedly just plain pretentious and unengaging and bad, and probably not helped at all by the man’s very gradual spiral into crippling dipsomania. (*See Footnote)

The tall, ungainly, socially challenged and hard-drinking Dr. Incandenza’s May-December marriage to one of the few bona fide bombshell-type females in North American academia, the extremely tall and high-strung but also extremely pretty and gainly and teetotalling and classy Dr. Avril Mondragon, the only female academic ever to hold the Macdonald Chair in Prescriptive Usage at the Royal Victoria College of McGill University, whom Incandenza’d met at a U. Toronto conference on Reflective vs. Reflexive Systems, was rendered even more romantic by the bureaucratic tribulations involved in obtaining an Exit- and then an Entrance-Visa for Professor Mondragon. The birth of the Incandenzas’ first child, Orin, had been at least partly a legal maneuver.

It is known that, during the last five years of his life, Dr. James O. Incandenza liquidated his assets and patent-licenses, ceded control over most of the Enfield Tennis Academy’s operations to his wife’s half-brother and devoted his unimpaired hours almost exclusively to the production of documentaries, technically recondite art films, mordantly obscure and obsessive, leaving behind a substantial (given the late age at which he bloomed, creatively) number of completed films, some of which have earned a small academic following for their technical feck and for a pathos that was somehow both surreally abstract and melodramatic at the same time.

Professor James O. Incandenza, Jr.’s untimely suicide at fifty-four was held a great loss in at least three world. President J. Gentle, acting on behalf of the O.N.R., conferred a posthumous citation. Cornell University Press announced plans for a festschrift. Certain leading young quote ‘après-garde’ and ‘anticonfluential’ filmmakers employed certain oblique visual gestures that paid the sort of deep-insider’s elegaic tribute no audience could be expected to notice. And those of E.T.A.’s junior players whose hypertrophied arms could fit inside them wore black bands on court for almost a year.

MONDAY NOV 2 1992

‘Hal?’

‘Yes Mario?’

‘Are you asleep?’

‘Booboo, I can’t be asleep if we’re talking.’

‘Boy were you on today. When he hit that one down the line and you got it and fell down and hit that drop-volley Pemulis said the guy looked like he was going to be sick all over the net.’

‘Boo, I kicked a kid’s ass is all. End of story. I don’t think it’s good to rehash it when I’ve kicked somebody’s ass. It’s like a dignity thing. I think we should just let it sort of lie in state, quietly. Speaking of which.’

‘Hey Hal?’

‘It’s late, Mario. It’s sleepy-time. Close your eyes and think fuzzy thoughts.’

‘You think I think fuzzy thoughts all the time. You let me room with you because you feel sorry for me.’

‘Booboo I’m not even going to dignify that. I’ll regard it as like a warning sign. You always get petulant when you don’t get enough sleep. And here we are seeing petulance already on the western horizon, right here.’

‘When I asked if you were asleep I was going to ask if you felt like you believed in God, today, out there, when you were so on, making that guy look sick.’

‘Really don’t think midnight in a totally dark room with me so tired my hair hurts and drills in six short hours is the time and place to get into this, Mario. You ask me this once a week.’

‘You never say, is why.’

‘So tonight to shush you how about if I say I have administrative bones to pick with God, Boo. I’ll say God seems to have a kind of laid-back management style I’m not crazy about. I’m pretty much anti-death. God looks by all accounts to be pro-death. I’m not seeing how we can get together on this issue, he and I, Boo.’

‘You’re talking about since Himself passed away.’

‘Mario, you and I are mysterious to each other. We countenance each other from either side of some unbridgeable difference on this issue. Let’s lie very quietly and ponder this.’

‘Hey Hal? How come the Moms never cried when Himself passed away? I cried, and you, even C.T. cried. I saw him personally cry.’

‘...’

‘Hey Hal, did the Moms seem like she got happier after Himself passed away, to you?’

‘...’

‘It seems like she got happier. She seems even taller. She stopped travelling everywhere all the time for this and that thing. The corporate-grammar thing. The library-protest thing.’

‘Now she never goes anywhere, Boo. Now she’s got the Headmaster’s House and her office and the tunnel in between, and never leaves the grounds. She’s a worse workaholic than she ever was. And more obsessive-compulsive. When’s the last time you saw a dust-mote in that house?’

‘Hey Hal?’

‘Now she’s just an agoraphobic workaholic and obsessive-compulsive. This strikes you as happification?’

‘Her eyes are better. They don’t seem as sunk in. They look better. She laughs at C.T. way more than she laughed at Himself. She laughs from lower down inside. She laughs more. Her jokes she tells are better ones than yours, even, now, a lot of the time.’

‘...’

‘How come she never got sad?’

‘She did get sad, Booboo. She just got sad in her way instead of yours and mine. She got sad, I’m pretty sure.’

‘Hal?’

‘She’s plenty sad, I bet.’

VERY LATE OCTOBER 1992

Hal Incandenza had this horrible new recurring dream where he was losing his teeth, where his teeth had become like shale and splintered when he tried to chew, and fragmented and melted into grit in his mouth; in the dream he was going around squeezing a ball and spitting fragments and grit, getting more and more hungry and scared. Everything in there loosened by a great oral rot that the nightmare's Teddy Schacht wouldn't even look at, saying he was late for his next appointment, everyone seeing Hal's crumbling teeth and looking at their watch and making vague excuses, a general atmosphere of the splintering teeth being a symptom of something way more dire and distasteful that no one wanted to confront him about.

WEDNESDAY NOV 4, 1992

CAMBRIDGE

From Cambridge’s Latinate Inman Square, Michael Pemulis, nobody’s fool at all, rides one necessary bus to Central Square and then an unnecessary bus to Davis Square and a train back to Central. This is to throw off the slightest possible chance of pursuit. At Central he catches the Red Line to Park St. Station, where he’s parked in an underground lot he can more than afford. The day is autumnal and mild, the east breeze smelling of urban commerce and the vague suede smell of new-fallen leaves. The sky is pilot-light blue; sunlight reflects complexly off the smoked-glass sides of tall centers of commerce all around Park St. downtown. Pemulis wears button-fly chinos and an E.T.A. shirt beneath a snazzy blue Brioni sport-coat, plus the bright white yachting cap that Mario Incandenza calls his Mr. Howell hat. The hat looks rakish even when turned around, and it has a detachable lining. Inside the lining can be kept portable quantities of just about anything. Having indulged in 150 mg. of very mild ‘drines, post-transaction. Wearing also gray-and-blue saddle oxfords w/o socks, it’s such a mild autumn day. The streets literally bustle. Vendors sell hot pretzels and tonics and those underboiled franks Pemulis likes to have them put the works on. You can see the State House and Common and Courthouse and Public Gardens, and beyond all that the cool smooth facades of Back Bay brownstones. The echoes in the underground Park PL garage—PARK—are pleasantly complex. Traffic westward on Commonwealth Avenue is light (meaning things can move) all the way through Kenmore Square and past Boston U. and up the long slow hill into Allston and Enfield.

After intricate third-party negotiations, Michael Pemulis finally landed 650 mg. of the vaunted and elusive compound DMZ. The incredibly potent DMZ is apparently classed as a para-methoxylated amphetamine but really it looks to Pemulis from his slow and tortured survey of MED.COM more similar to the anticholinergic-deliriant class, Way more powerful than mescaline or MDA or DMA or TMA or MDMA or DOM or STP or the I.V.-ingestible DMT (or Ololiuqui or datura’s scopolamine, or Bufotenine) or Ebene or psilocybin; DMZ resembling chemically some miscegenation of a lysergic with a muscimoloid, but significantly different from LSD-25 in that its effects are less visual and spatially-cerebral and more like temporally-cerebral, with some sort of manipulated- phenylkylamine-like speediness whereby the ingester perceives his relation to the ordinary flow of time as radically (and euphorically) altered. The incredibly potent DMZ is synthesized from a derivative of fitviavi, an obscure mold that grows only on other molds, by the same ambivalently lucky chemist at Sandoz Pharm. Who’d first stumbled on LSD while futzing around with ergotic fungi on rye. DMZ’s discovery was the tail-end of the 960s. A substance even just the accidental-synthesis of which sent the Sandoz chemist into early retirement and serious unblinking wall-watching, the incredibly potent DMZ has a popular-lay-chemical-underground reputation as the single grimmest thing ever conceived in a tube. It is also now the hardest recreational compound to acquire in North America after raw Vietnamese opium, which forget it.

DMZ is sometimes also referred to in some metro Boston chemical circles as Madame Psychosis, after a popular very-early-morning cult radio personality on M.I.T.’s student-run radio station WYYY-109, ‘Largest Whole Prime on the FM Band,’ which Mario Incandenza listens to almost religiously.

The day-shift Ennet House kid at the booth who raises the portcullis to let him onto the grounds had a couple times in October approached Pemulis about a potential transaction. Pemulis has a rigid policy about not transacting with E.T.A. employees who come up the hill from the halfway house, since he knows some of them are at the place on Court Order, and knows for a fact they pull unscheduled Urines all over the place down there; and his basic attitude with these low-rent employees is one of unfoolish discretion and like why tempt fate.

The East Courts are empty and ball-strewn when Pemulis pulls in; most of them are still at lunch. Pemulis, Troeltsch, and Schacht’s triple-room is in subdorm B and superjacent to the Dining Hall, from which through the floor Pemulis can hear voices and silverware and can smell exactly what they’re having. The first thing he does is phone Mario’s room, where Hal is sitting in windowlight with the Riverside Hamlet he told Mario he’d read and help with a conceptual film-type project based on part of, eating an AminoPal® energy-bar and waiting very casually, the phone already out lying ready on the arm of the chair with two SAT-prep guides. Hal deliberately waits till the third ring.

‘Mmyellow.’

‘The turd emergeth.’ Pemulis’s clear and digitally condensed voice on the line. ‘Repeat. The turd emergeth.’

‘Please commit a crime,’ is Hal Incandenza’s immediate reply.

‘Gracious me,’ Pemulis says into the phone tucked under his jaw, carefully de-Velcroing the lining of his Mr. Howell hat.

Michael Pemulis has this habit of looking first to one side and then over to the other before he says anything. It’s impossible to tell whether this is unaffected or whether Pemulis is emulating some film-noir-type character. It’s worse when he’s put away a couple ‘drines. He and Trevor Axford and Hal Incandenza are in Pemulis’s room, stroking their chins, looking down at Michael Pemulis’s yachting cap on his bed. Lying inside the overturned hat are a bunch of fair-sized but bland-looking tablets of the allegedly incredibly potent DMZ.

Pemulis looks all around behind them in the empty room. ‘This, Incster, Axhandle, is the incredibly potent DMZ. The Great White Shark of organo-synthesized hallucinogens. ‘The gargantuan feral infant of—’

Hal says ‘We get the picture.’

‘The Yale U. of the Ivy League of Acid,’ says Axford.

‘Your ultimate psychosensual distorter,’ Pemulis sums up.

‘Think you mean psychosensory, unless I don’t know the whole story here.’

Axford gives Hal a narrow look. Interrupting Pemulis means having to watch him do the head-thing all over again each time.

‘Hard to find, gentlemen. As in very hard to find. Last lots came off the line in the early 70s. These tablets here are artifacts. Certain amount of decay in potency probably inevitable. Used in certain shady CIA-era military experiments.’

Axford nods down at the hat. ‘Mind-control?’

‘More like getting the enemy to think their guns are hydrangea, the enemy’s a blood-relative, that sort of thing. Who knows. The accounts I’ve been reading have been incoherent, gistless. Experiments conducted. Let’s just say things got out of control. Potency judged too incredible to proceed. Subjects locked away in institutions and written off as casualties of peace. Formula shredded. Research team scattered, reassigned. Vague but I’ve got to tell you pretty sobering rumors.’

‘These are from the early 70s?’ Axhandle says.

‘See the little trademark on each one, with the guy in bell-bottoms and long sideburns?’

‘Is that what that is?’

‘Unprecedentedly potent, this stuff. The Swiss inventor they say was originally recommending LSD-25 as what to take to come down off the stuff.’ Pemulis takes one of the tablets and puts it in his palm and pokes at it with a callused finger. ‘What we’re looking at. We’re looking here at either a serious sudden injection of cash—’

Axford makes a shocked noise. ‘You’d actually try to peddle the incredibly potent DMZ around this sorry place?’

Pemulis’s snort sounds like the letter K. ‘Get a large economy-size clue, Axhandle. Nobody here’d have any clue what they’d even be dealing with. Not to mention be willing to pay what they’re worth. Why, there are pharmaceutical museums, left-wing think tanks, New York designer-drug consortiums I’m sure’d be dying to dissect these. Decoct like. Toss into the spectrometer and see what’s what.’

‘That we could get bids from, you’re saying,’ Axford says. Hal squeezes a ball, silently looking at the hat.

Pemulis turns the tablet over. ‘Or certain very progressive and hip-type nursing homes. Or down at Back Bay at that yogurt place with that picture of those historical guys Inc was saying at breakfast was up on the wall.’

‘Ram Das. William Burroughs.’

‘Or just down in Harvard Square at Au Bon Pain where all those 70s-era guys in old wool ponchos play chess against those little clocks they keep hitting.’

Axford’s pretending to punch Hal’s arm in excitement.

Pemulis says ‘Or of course I’m thinking I could just go the sheer-entertainment route and toss them in the Gatorade barrels at the meet with Port Washington Tuesday, or down at the WhataBurger—watch everybody run around clutching their heads or whatever. I’d be way into watching Wayne play with distorted senses.’

Hal puts one foot up on Pemulis’s little frustum-shaped bedside stool and leans farther in. ‘Would it be prying to ask how you finally managed to get hold of these?’

‘It wouldn’t be prying at all,’ Pemulis says, removing from the yachting cap’s lining every piece of contraband he’s got and spreading it out on the bed, sort of the way older people will array all their valuables in quiet moments. He has a small quantity of personal-consumption Lamb’s Breath cannabis (bought back from Hal out of a 20-g. he’d sold Hal) in a dusty baggie, a little Saran-Wrapped cardboard rectangle with four black stars spaced evenly across it, the odd ‘drine, and it looks like a baker’s dozen of the incredibly potent DMZ, Sweet Tart-sized tablets of no particular color with a tiny mod hipster in each center wishing the viewer peace. ‘We don’t even know how many hits this is,’ he muses quietly. There’s sun on the wall and an enormous hand-drawn Sierpinski gasket. In one of the three big mullioned west windows there’s an oval flaw that’s casting a bubble of ale-colored autumn sunlight from the window’s left side to elongate onto Pemulis’s tightly made bed (one of the prorectors' tasks is to go around to different Subdorm floors and check for things like are the beds made up drum-tight, with unpleasant little extra drills added to the regimens of bed-making and toothpaste-cap-replacing slackers, though few of the prorectors have the combination anality and drive actually to go around to their assigned rooms with a checklist, the exception being Aubrey deLint, who's got the Pemulis/ Troeltsch/Schacht suite under extremely beady scrutiny at all times). He moves everything his hat’s got into the brighter bubble, going down on one knee to study a tablet between his forceps (Pemulis owns stuff like philatelic forceps, a loupe, a pharmaceutical scale, a postal scale, a personal-size Bunsen burner) with the calm precision of a jeweler. ‘The literature’s mute on the titration. Do you take one tablet?’ He looks up on one side and then back around on the other at the boys’ faces leaning in above. ‘Is like half a tab a regulation hit?’

‘Two or even three tablets, maybe?’ Hal says, knowing he sounds greedy but unable to help himself.

‘The accessible data’s vague,’ Pemulis says, his profile contorted around the loupe in his socket. ‘The literature on muscimole-lysergic blends is spotty and vague and hard to read except to say how massively powerful the supposed yields are.’

Hal looks at the top of Pemulis’s head. ‘Did you hit a medical library?’

‘I went back and forth and up and down through MED.COM. Plenty on lysergics, plenty on methoxy-class hybrids. Vague and almost gossip-columny shit on fitviavi-compounds. To get anything you got to cross-key Ergotics with the phrase muscimole or muscimolated. Only a couple things ring the bell when you key in DMZ. Then they’re all potent this, sinister that. Nothing with any specifics. And jumbly polysyllables out the ass. Whole thing gave me a migraine.’

‘Yes but did you actually go to a real med-library?’ Hal’s his mother Avril’s child when it comes to databases. Axford now really does punch him once in the shoulder, albeit the right one. Pemulis is scratching absently at the little hair-hurricane at the center of his hair. It’s close to 1430h., and the flawed bubble of light on the bed is getting to be the slightly sad color of early winter P.M. There are still no sounds from the West Courts outside, but there’s high song of much volume through the wall’s water-pipes—a lot of the guys who are drilled past caring in the A.M. don’t get to shower until after lunch, then sit through P.M. classes with wet hair and different clothes than their A.M. classes.

Pemulis rises to stand between them and looks around the empty three-bedded room again, with neat stacks of three players’ clothes and bright gear on shelves and three wicker laundry hampers bulging slightly. There is the rich scent of athletic laundry, but other than that the room looks almost professionally clean. Pemulis and Schacht’s room makes Hal and Mario’s room look like an insane asylum, Hal thinks.

Pemulis still has his cheek screwed up to keep the loupe in as he looks around. ‘One monograph had this toss-off about DMZ where the guy invites you to envision acid that has itself dropped acid.’

‘Holy crow.’

‘One article talks about how this one Army convict at Leavenworth got allegedly injected with some massive unspecified dose of early DMZ as part of some Army experiment in Christ only knows what and about how this convict’s family sued over how the guy reportedly lost his mind.’ He directs the loupe dramatically at first Hal and then Axford. ‘I mean literally lost his mind, like the massive dose picked his mind up and carried it off somewhere and put it down someplace and forgot where.’

‘I think we get the picture, Mike.’

‘Allegedly the guy’s found later in his Army cell, in some impossible lotus position, singing show tunes in a scary deadly-accurate Ethel-Merman-impression voice.’

The slackening of a cheek lets the loupe fall out and bounce off the drum-tight bed, and Pemulis gets it to rebound into his palm without even looking. ‘I think we can err on the side of not dickying the Gatorade barrels, anyway. This soldier’s story’s moral was proceed with caution, big time. The guy’s mind’s still allegedly AWOL. An old soldier, now, still belting out Broadway medleys in some secretive institution someplace. Blood-relatives try to sue on the guy’s behalf, Army apparently came up with enough arguments to give the jury reasonable doubt about if the guy can even be said to legally exist enough to bring suit, anymore, since the dose misplaced his mind.’

Axford feels absently at his elbow. ‘So you’re saying let’s proceed with care why don’t we.’

Hal kneels to prod one of the tablets up against the dusty baggie’s side. His finger looks dark in the elongated bubble of light. ‘I’m thinking these look like two tablets are possibly a hit. A kind of Motrinish look to them.’

‘Visual guesswork isn’t going to do it. This is not Bob Hope, Inc.’

‘We could even designate it “Ethel,” for on the phone,’ Axford suggests.

Pemulis watches Hal arranging the tablets into the same general cardioid-shape as E.T.A. itself. ‘What I’m saying. This is not a fools-rush-in-type substance, Inc. This show-tune soldier like left the planet.’

‘Well, so long as he waves every so often.’

‘The sense I got is the only thing he waves at is his food.’

‘But that was from a massive early dose,’ Axford says.

Hal’s arrangement of the tablets on the red-and-gray counterpane is almost Zen in its precision. ‘These are from the 70s? ’

Over the course of the next academic day—the incredibly potent stash now wrapped tight in Saran and stashed deep in the toe of an old sneaker that sits atop the aluminum strut between two panels in subdorm B’s drop ceiling, Pemulis’s time-tested entrepot — over the course of the next day or so the matter’s hashed out and it’s decided that it’s really Pemulis and Axford and Hal’s right — duty, almost, to the spirits of inquiry and good trade practice — to sample the potentially incredibly potent DMZ in predeterminedly safe amounts before unleashing it on any unwitting civilians. Pemulis’s mark-up isn’t anything beyond accepted norms, and there’s always room in Hal’s budget for spirited inquiry. Hal’s one condition is that somebody verify that the compound is both organic and nonaddictive, which Pemulis says a physical hands-on library assault is already down in his day-planner in pen, anyway.

Pemulis finally nixes the notion of performing the spirited controlled experiment here in Enfield, where Axford has to be at the A squad’s dawn drills every morning at 0500, and also Hal. Pemulis posits that a solid 36 hours of demand-free time will be advisable for any interaction with the incredibly potent you-know-whatski. That also lets out the inter-academy thing with Port Washington tomorrow, for which Charles Tavis has chartered two buses, because so many E.T.A. players are getting to go and do battle in this one—Port Washington Academy is gargantuan, the Xerox Inc. of North American tennis academies, with over 300 students and 64 courts—so many that Tavis will almost surely go ahead and bus them all back up from Long Island just as soon as the post-competition dance is over, rather than shell out for all those motel rooms without corporate support. This E.T.A.-P.W. meet and buffet and dance are a private, inter-academy tradition, an epic rivalry almost a decade old. Plus Pemulis says he’ll need a couple weeks of quality med-library-stacks-tossing time to do the more exacting titration and side-effects research Hal agrees the soldier’s sobering story seems to dictate. So, they conclude, the window of opportunity looks to be 11/20-21—the weekend right after the big End-of-Fiscal-Year fundraising exhibition, before Thanksgiving week and the WhataBurger Invitational in sunny AZ, because this year in addition to Friday 11/20 they also get Saturday 11/21 off, as in from both class and practice, then the E.T.A.s will get Saturday to rest and recharge before starting both the pre-WhataBurger training week and the bell-lap of prep for 12/12’s Boards, meaning late Friday night-Sunday A.M. will give Pemulis, Hal, and Axford enough time to psychospiritually rally from whatever meninges-withering hangover the incredibly potent DMZ might involve...and Axford predicted it would be a witherer indeed, since even just LSD alone left you the next day not just sick or down but utterly empty, a shell, void inside, like your soul was a wrung-out sponge. Hal wasn’t sure he concurred. An alcohol hangover was definitely no frolic in the psychic glade, all thirsty and sick and your eyes bulging and receding with your pulse, but after a night of involved hallucinogens Hal said the dawn seemed to confer on his psyche a kind of pale sweet aura, a luminescence. Halation, Axford observed.

THURSDAY NOV 5 1992

The phone sounded from somewhere under the hill of bedding as Hal was on the edge of the bed with one leg up and his chin on its knee, clipping his nails into a wastebasket that sat several meters away in the middle of the room.

‘Mmmyellow.’

‘Mr. Incredenza, this is the Enfield Raw Sewage Commission, and quite frankly we’ve had enough shit out of you.’

‘Hello Orin.’

‘How hangs it, kid.’

‘Interesting you should call just now. Because I’m clipping my toenails into a wastebasket several meters away.’

‘Jesus, you know how I hate the sound of nail clippers.’

‘Except I’m shooting seventy-plus percent. The little fragments of clipping. It’s uncanny. I keep wanting to go out in the hall and get somebody in here to see it. But I don’t want to break the spell.’

‘The fragile magic-spell feel of those intervals where it feels you just can’t miss.’

‘It’s definitely one of those can’t-miss intervals. It’s just like that magical feeling on those rare days out there playing. Playing out of your head, deLint calls it. Being in The Zone. Those days when you feel perfectly calibrated.’

‘Coordinated as God.’

‘Some groove in the shape of the air of the day guides everything down and in.’

‘When you feel like you couldn’t miss if you tried to.’

‘These can’t-miss intervals make superstitious natives out of us all, Hal-lie. You don’t know true bug-eyed athletic superstition till you hit the pro ranks. Jock straps unwashed game after game until they stand up by themselves in the overhead luggage compartments of planes. Bizarrely ritualized dressing, eating, peeing. Then there are the NFL players who write down exactly what they say to everybody before a game, so if it’s a magical can’t-miss-type game they can say exactly the same things to the same people in the same exact order before the next game.’

‘The phone’s no longer wedged under my jaw. I can even do it one-handed, holding the phone in one hand. But it’s still the same foot.’

‘I can hear those clippers. Quit with the clippers a second.’

‘This is the big moment. I’ve totally exhausted the left foot finally and am switching to the right foot. This’ll be the real test of the fragility of the spell.’

‘This all wasn’t even why I originally called. Let me ask you a couple questions. Hallie, I’ve got somebody from Moment fucking magazine out here doing a quote soft profile.’

‘You’ve got what?’

‘A human-interest thing. On me as a human. Moment doesn’t do hard sports, this lady says. They’re more people-oriented, human-interest. It’s for something called quote People Right Now, a section.’

‘Moment’s a supermarket-checkout-lane-display magazine. It’s in there with the rodneys and gum. It’s all over C.T.’s waiting room. They did a thing on the little blind Illinois kid Dymphna that Thorp thought so well of.’

‘Hallie, this physically imposing Moment girl’s asking all these soft-profilesque family-background questions.’

‘She wants to know about Himself?’

‘Everybody. You, the Mad Stork Himself, the Moms. It’s gradually emerging it’s going to be some sort of memorial to the Stork as patriarch, everybody’s talents and accomplishments profiled as some sort of refracted tribute to el Storko’s careers.’