ACROSS THE UNIVERSE

Was a Malaysian interpreter the first person to travel around the Earth?

Filed Under: Unintended Consequences of Capitalism

1. Veni, vidi, vici

Like most Americans, I was taught in elementary school that in the year 1519, the explorer Ferdinand Magellan left Spain with five ships and sailed westward across the Atlantic Ocean until he reached the Pacific Ocean, and kept sailing west until he went all the way around the world, returning to Spain three years later a hero—the first person to circumnavigate the Earth. I remember tracing the route of Magellan around the continents along the bumpy surface of the classroom globe with my finger, thinking about that powerful sounding word, circumnavigate. As a child, the narrative of Magellan, Conqueror of the Seas was irresistibly seductive.

Part of the power of this simple, bogus version of the story is that it is so thoroughly denatured that all that’s left is the classic Hero’s Journey. Called to adventure by the powerful forces of God and Country, Magellan crosses the threshold into the unknown. While in the Abyss, he overcomes a series of trials and ordeals to win the prize, a western route to the Spice Islands. Magellan is transformed into, as mythologist Joseph Campbell would say, the Master of Two Worlds. Magellan’s name eventually became synonymous with the concept of exploration itself, demonstrated by his eponyms: the Strait of Magellan, the Magellanic Clouds, NASA’s Magellan spacecraft, and the Giant Magellan Telescope, among others.

2. Enrique de Malacca

The actual story is far more convoluted, treacherous, and brutal. For starters, Fernão de Magalhães wasn’t Spanish, but an aging Portuguese soldier with a bad leg who had spent his entire life fighting his way across India, Southeast Asia, and North Africa in support of the expanding Portuguese Empire. Magellan’s greatest accomplishment prior to the circumnavigation was serving under Portuguese General Afonso de Albuquerque during the siege of the Malaysian port of Malacca in 1511, a city that became a foothold for the Portuguese entry into the system of spice trading that had been dominated by Arab, Chinese, and Indian merchants for over a millennium.

Following the capture of Malacca, Portuguese soldiers plundered gold and silver and a number of slaves. At this time, Magellan acquired an adolescent slave about 14 years old to serve as his interpreter and servant. A devout Catholic, Magellan had the boy baptized and christened him Enrique.

Enrique de Malacca, as he came to be known, accompanied Magellan on the long return voyage to Portugal in 1513, a route that took them over halfway around the world. But to a boy kidnapped and pressed into service by a foreign soldier, and then packed into a rank, filthy ship for god-knows-how-long, this “Portugal” might as well have been across the universe.

3. Insider Information

Magellan’s idea for an expedition to the Spice Islands probably originated in letters he received from his cousin and former shipmate Francisco Serrão, who had become the first Portuguese explorer to reach the Spice Islands in 1512. Serrão wrote to Magellan of their beauty and fantastic abundance of nutmeg, mace, cloves, and pepper. As a minor Portuguese noble and a decorated veteran of multiple wars who had been wounded in battle, Magellan felt entitled to petition King Manuel I of Portugal to fund his idea for an expedition to the Spice Islands. But Manual I, irritated by Magellan’s air of entitlement and requests for money, rejected his proposal—three times.

Humiliated by the Portuguese king, Magellan renounced his Portuguese citizenship in 1517 and followed in the footsteps of Christopher Columbus by taking his plan straight to the Spanish monarchy instead. In January of 1518, Magellan and Enrique arrived at the royal court in Valladolid to petition the eighteen-year-old King of Spain, Charles I, to back a western expedition to the Spice Islands. Charles I, heir to Hapsburg Dynasty, had only the year before left his birthplace in Flanders to become the newly crowned King of Spain (itself a new nation formed by the unification of Aragón, Castile, and Navarra). Magellan presented Charles with maps and sworn documents, and introduced Enrique de Malacca, who was dressed up for the part in colorful Malaysian garb.

In order to lend more credibility to the venture, Magellan tried to deceive Charles by playing on the similarity between the name of the port city of “Malacca” and the name for the Spice Islands, the “Moluccas,” to imply that Enrique was a native of the Spice Islands, which he was not. In reality, Malacca was over a thousand miles away from the Spice Islands. One paradox of venture capital is that you often have to straight up lie about your business model in order to get the investment capital to actually develop the technology you were lying about already having.

Whether or not this worked is anyone’s guess. From Charles’ perspective, Magellan had something much, much more highly prized in the world of venture capital than simply a good idea.

Magellan had insider information.

During his military career in Portugal, Magellan had purportedly seen a closely guarded map in the King of Portugal’s treasury drawn by German cartographer Martin of Bohemia. This map depicted a concealed strait at the tip of South America: an open passage to the west. According to Antonio Pigafetta, an Italian nobleman who wrote a detailed firsthand account of the expedition, without this map it would have been impossible for Magellan to have found the entrance to what he described as a “well-hidden strait” now known as the Strait of Magellan.

Magellan was ultimately able to convince the eighteen-year-old King of Spain to finance a western expedition to the Spice Islands, infuriating the head of the House of Commerce, Bishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, and the entire Spanish establishment. The King generally did not pay for Spanish expeditions to the New World. (Hernán Cortés went deeply into personal debt in order to mount his conquest of Mexico in 1519, which ultimately delivered the wealth of the Aztec Empire to Charles.) Beyond that, this Fernão de Magalhães was clearly a turncoat. How could he be trusted?

But the King would not be deterred. Charles appointed Magellan admiral of the Spanish fleet and gave him the power of “rope and knife” over the crew, many of whom were highly skeptical of their new Portuguese captain.

4. First to Circumnavigate Me

This brings us to a second major problem with the Magellan, Conqueror of the Seas narrative: Fernão de Magalhães never sailed around the Earth. Only about two-thirds of it, actually.

Magellan died on April 27th, 1521, on the beach of Mactan Island in the Philippines, 13,000 miles short of his goal, in a battle that Magellan instigated in order to forcibly convert the inhabitants to Christianity. Although his officers begged him to abandon unnecessary aggression in favor of diplomacy, Magellan, blinded by past success and believing that God would protect him, wouldn’t listen. Magellan ordered his men to burn down the nearest village, enraging one of Mactan’s chiefs, Lapu-Lapu, who returned with a massive army of over a thousand warriors. Magellan was cut to ribbons, and nothing of him was ever recovered, not even his armor. Karma can be a real bitch.

Out of the five boats and 270 men that set sail in 1519, just one, the Victoria, captained by Juan Sebastián Elcano and carrying just 18 emaciated crew members managed to circumnavigate the Earth and return to Spain. As a haggard and malnourished Elcano set anchor in Seville on September 8, 1522, with a fortune of over 26 tons of cloves and cinnamon, the Victoria fired off its artillery to announce their return. King Charles awarded Elcano with a coat of arms depicting a globe with the motto Primus circumdedisti me, first to circumnavigate me. Wishing to avoid the same type of corporate espionage that likely made the circumnavigation possible in the first place, the king immediately confiscated the records and maps made during the voyage (which is now officially referred to as the Magellan-Elcano circumnavigation).

5. Air dicincang tidak akan putus (Chop the water, the water still flows)

— Malaysian proverb about family bonds

Enrique de Malacca, however, was not among the 18 men on the Victoria who returned Seville in September of 1522.

At the time of Magellan’s death, Enrique had served his master for a decade, risking his life countless times. Enrique had actually been wounded on the beach in the Battle of Mactan that claimed Magellan’s life. This loyalty was ultimately rewarded in Magellan’s will, which stated unequivocally that in the event of his death, Enrique de Malacca was to be manumitted (legally freed from slavery) immediately. But the newly elected captains of the expedition, Duarte Barbosa and João Serrão, flatly refused to free him, declaring that Enrique was still a slave and would be flogged unless he obeyed their orders. This betrayal seems to have broken something inside of Enrique.

Shortly after the Battle of Mactan, Enrique de Malacca—the only person who could understand a word of the local language, Cebuano—was ordered by Barbosa and Serrão to return to shore and negotiate with the local leaders about reparations for Magellan’s death.

Enrique returned bearing an invitation from the islanders to a grand feast to be thrown in honor of the Spanish officers and their fallen captain, at which they would be presented with gemstones and other lavish gifts. The Spanish officers bought the almost painfully obvious ruse, hook, line, and sinker. After the Spanish officers were plied with food and drink, Cebuano warriors stormed in and promptly massacred the entire landing party, with one exception: Enrique de Malacca, who not only managed to survive but to escape his Spanish captors. And then he vanished.

Was Enrique de Malacca the architect of the ambush that killed the Spanish officers, or merely an unwitting beneficiary? Where did he go after outwitting his captors? It’s unlikely we will ever know.

So I leave it to you, dear reader: after being kidnapped as a child, taken to a distant land to meet the king, cheating death countless times, and orchestrating a fantastic escape from your captors, where would you go?

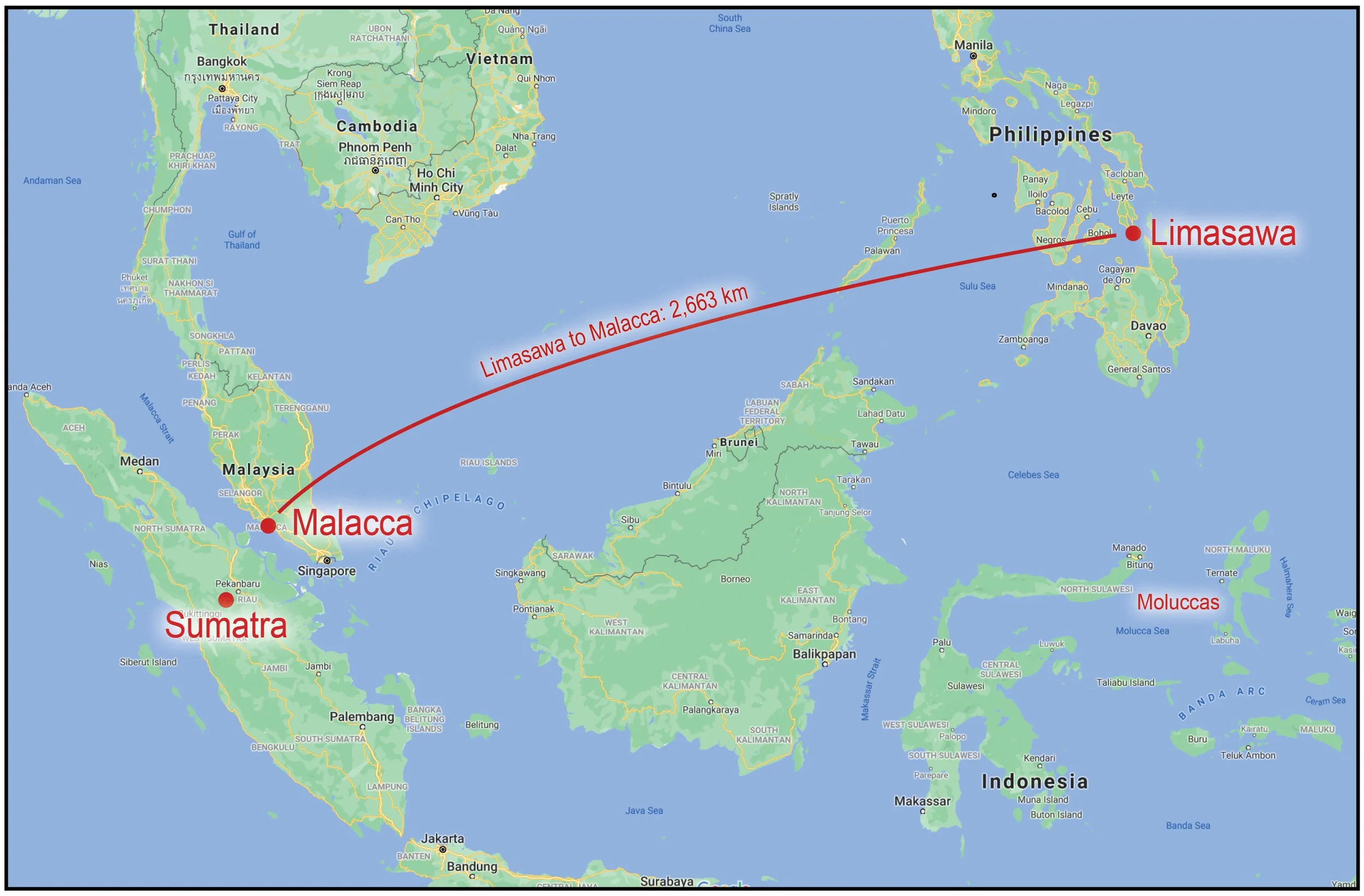

The consensus answer is home. Given that Enrique was in his early twenties, many members of his family would have still been alive. Enrique escaped the Spanish about 1650 miles northeast of Malacca, the Malaysian port where Magellan acquired him as a slave in 1511. Although island hopping on ships headed towards Malacca would have taken him a month or two, it was a mere fraction of the distance of the Victoria’s return trip to Spain.

Historian John Sailors’ map illustrating the additional distance of 2,663 km (~1650 miles) that Enrique de Malacca would have had to travel in order to return to his starting point, the port of Malacca, and become the first person to circumnavigate the Earth in 1521.

Which begs the question:

If Enrique returned to Malacca before the Victoria arrived in Spain in September of 1522, 15 months later, does that mean a Malaysian, rather than a European, was the first person to travel around the Earth? And what would that mean?

* * * *

To many people in Malaysia and the Philippines, the story Enrique de Malacca’s 1521 circumnavigation is at least familiar, if not old news. In fact, the debate on the subject tends to center not on whether or not Enrique de Malacca was the first person travel around the world, but whether he was a Malaysian or Cebuano. According to Fred Magdalena, assistant director of the University of Hawaii Center for Philippine Studies, who has written extensively about Enrique’s identity, he in now woven into the cultural consciousness of Millennials and young people in particular. Streets named in his honor, statues depicting his (fully imagined) likeness, museum exhibits tracing his travels, and children’s books like First Around the Globe: The Story of Enrique have turned Enrique de Malacca into a Malaysian and Filipino icon, both as an explorer and as a tacit rejection of European Colonialism. Magdalena, John Sailors, and other Magellan scholars have recently called attention to the importance of incorporating Enrique into our understanding of how Colonialism unfolded in Malaysia and the Philippines, irrespective of claims to the title of first circumnavigator.

6. A Brief History of World-Systems Theory

Enrique de Malacca’s improbable journey from the edge of the Spanish empire to the court of Charles I and back again was only possible because of a transformation in the world that started a few decades earlier, around 1450: the emergence of the first truly global Capitalist economic system. Fragile and tenuous in its infancy, over the next 500 years it would become spectacularly successful, eventually maturing into the version of Industrial and Financial Capitalism we all know and love.

Many theories account for Capitalism’s rise, but only one provides a coherent explanation for how this system came into being, how it actually works in the past and in the present, and what will happen to it in the 21st century: world-systems theory.

World-systems theory, the brainchild of economic historian and sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein, considers the past 500 years of global social and economic change as a single, coherent phenomenon: the expansion of the Capitalist world-system. One of the advantages of world-systems theory is that if focuses on transnational institutions, long-lived economic patterns—the insatiable desire for more sugar in our foods, for instance—that can be more powerful than individual nation states. Wallerstein likened a world-system to an organism that is born, has a normal life, and dies when its internal problems (contradictions) become too great to resolve:

A world-system is a social system, one that has boundaries, structures, member groups, rules of legitimation, and coherence. Its life is made up of the conflicting forces which hold it together by tension and tear it apart as each group seeks eternally to remold it to its advantage. It has the characteristics of an organism, in that is has a life span over which its characteristics change in some respects and remain stable in others.

World-systems theory divides the countries of the world into three categories: core nations, periphery nations, and semi-periphery nations. Rich, technologically advanced countries with highly developed infrastructure and militaries are the core. Poor (but often resource-rich) countries that lack technology sectors, infrastructure, or large militaries are called the periphery. Countries with semi-developed infrastructure, technology, and militaries are the semi-periphery.

This highlights the nature of the core-periphery relationship: it is exploitative and based on unequal exchange. Unequal exchange is Wallerstein’s polite term for the core’s use of military dominance to extract land, labor, natural resources, taxes, and unfavorable trade agreements from the periphery and semi-periphery. Most often, it is enforced by coercion or sanctions, with cores applying full-scale violence when deemed necessary. Unequal exchange is not unlike organized crime, but on a vastly larger scale.

Raw materials or commodities extracted from the periphery are sent to semi-periphery countries, where they are processed or used to manufacture components by low-wage laborers. These cheap inputs are finally sent to the core, where they are used to make and sell high value consumption goods sold for an immerse profit (think about the Apple iPhone, built with cobalt mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo and assembled with low-wage labor in China by a company with corporate headquarters and major shareholders located in the US).[1] High value consumption goods are also introduced to new markets in the semi-periphery and periphery, where many of their components originated.

The example of world-systems theory that most people are familiar with is the system of “Triangular Trade” we are taught in high school history, another academically whitewashed term for the Transatlantic Slave Trade, in which slaves from West Africa were sent to the New World to produce commodities such as sugar, tobacco, and cotton, while Europe high value exchange goods such as textiles, guns, and alcohol moved in the opposite directions. It is significantly more complicated (Wallerstein’s Modern World-System series ran to four massive volumes, and he died with plans for two more), but you get the picture.

7. Economic Zombies Hungry for Gaaaaiiins

According to world-systems theory, what distinguishes Capitalism specifically from all previous economies is not wage labor, or markets, or stock corporations, all of which were normal parts of commerce prior to the 1500s. What distinguishes Capitalism is its establishment of a global division of labor. Similar to the division of labor that we are familiar with at home or at work (assigning different tasks to different people), a global division of labor separates the work done by entire industries into many different components, each performed in the part of the world where it is cheapest to perform that task. If you think about all the names of the countries on the “Made In” tags on pieces of clothing you’ve owned since you were young, you come up with a pretty decent picture of how the global division of labor in garment manufacturing, for instance, has shifted during your lifetime.

This frenetic, sleepless profit maximalization is why Capital is said to “flee” wherever the cost of labor, materials, and regulations are lowest, like a ravenous economic zombie scouring the world for gains. In an interview, the anthropologist Sidney Mintz, author of Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History, once said that Capital will reach a point in time when it has nowhere to run. Until I started working on this essay, I never really understood what he meant or what it implied. Naïvely, my assumption was that the idea that Capital was “running out of world” reflected the destruction of the environment or the exhaustion of natural resources. And to some degree, it does. But what Mintz is actually describing is the point at which there is nowhere left in the world-system for Capitalists to invest and improve their rate of profit, the ratio of profit to investment.

Economists have been debating for a hundred and fifty years whether or not there actually is a tendency of the rate of profit to fall (referred to as the “TRPF”), which a noted German economist speculated might be the fundamental contradiction at the heart of Capitalism. And indeed, until recently, any tendency for the rate of profit to fall has been kept in check by the economic “windfalls” created by slavery and Colonialism, unequal exchange between cores and peripheries, by cheap and abundant oil energy, and by a general lack of environmental or resource constraints. But there are few if any peripheries left to pull into the Capitalist world-system and give it some juice. Global ecological catastrophe is now visible on the horizon. Without the ability to dramatically increase labor exploitation, without access to “free real estate,” and without the ability to ignore or bypass concrete environmental and resource limits, the Capitalist world-system will at best stagnate.

* * * *

Given enough time, the most terrifying and destructive forces in the universe, black holes, eventually radiate away their heat and evaporate into nothing.

8. When Sheep Ate Men

Up until the 1400s, Spain (then a collection of kingdoms) and indeed the whole of feudal Western Europe was peripheral to the great empires of the east, who viewed Europe, to quote anthropologist David Graeber, as an “obscure and uninviting backwater full of religious fanatics.” Yet by 1540, Spain ruled over most of the Western Hemisphere and had pioneered the expansion of the first Capitalist world-system. What happened in the interregnum between Feudalism and Capitalism?

During the 1300 and 1400s, Europe was wracked by a series of crises on all fronts. The Black Plague, peasant revolts, and centuries of endemic warfare had left over a third of the population dead. Elites began to enclose (fence off) common agricultural lands that peasants had subsisted on for generations, or convert them to sheep grazing lands, causing a drop in cereal production that led to episodic famines in the countryside—the origin of the term when sheep ate men. Enclosure and lack of economic opportunity pushed the rural population into wage labor in urban centers. The landed nobility scrambled to find new sources of revenue to replace their labor, but within mainland Europe, conquest and dispossession had their limits.

One effect of increasing urbanization, which tended to cluster along maritime routes, was the widespread dissemination of improved engineering and shipping technologies which would help resolve the economic crises caused by the breakdown of feudalism and the natural limits of territorial expansion in mainland Europe. The explosive growth of the Capitalist world-system would not have been possible at this particular moment without the appearance of the mariner’s astrolabe and magnetic compass, rudders and square rigging, rollable cast-iron cannons of different calibers that could be used to create massive, floating cargo-fortresses like the Portuguese Carrack and the Spanish Galleon, the massive ships that eventually carried millions of slaves across the Atlantic. And of course double-entry bookkeeping to keep track of the profits.

With these key technologies in play, the first step in world-system building was for the aspiring core countries of Western Europe (here Portugal and Spain, but later, the Netherlands, England, France) to bring all the land and resources and people “outside of Capital” into Capital, that is, to identify every potentially productive resource in the world and then establish ways of making them profitable. To do this, the aspiring core countries would have to map the world, and in order to map the world they would have to be able to traverse it, and in order to traverse it, captains, sailors, and wealthy investors had to believe that such trips were possible—which is where Magellan fits into this foundational process of primitive accumulation. Primitive accumulation is a polite term for the “discovery,” dispossession, and exploitation of the periphery and semi-periphery by the core. As a noted German economist chillingly described it over a hundred and fifty years ago:

The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signaled the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief moments of primitive accumulation.

Primitive accumulation is not a process that only happened far in the past, but one that continues today. Israel’s genocide and dispossession of Palestinians in Gaza over the past eight decades is a prime example of primitive accumulation and the dehumanization it entails.

9. The Pilot Test

The Portuguese expansion into the Atlantic Ocean was the pilot test for the Capitalist world-system which emerged during the following century. Because of its lengthy border along the Atlantic and lack of critical raw materials like timber, during the 1400s Portugal became first European country to invest heavily in new types of ships and maritime technology, pushing outward towards islands in the Atlantic Ocean (Madéira, Santiago de Cabo Verde, and São Tomé) and further and further south along the coast of West Africa. Atlantic Islands like Madéira, (which means timber in Portuguese), an uninhabited piece of “free real estate” that Portugal claimed in 1419, had the perfect climate for sugar cane agriculture. Sugar was worth a fortune, but its production was terribly labor intensive and ecologically destructive. European colonists and indentured servants were also unable to survive the tropical diseases and harsh working conditions of the sugar plantations, or roças.

But the Portuguese monarchy soon hit on a solution to its labor crisis: revive chattel slavery in the periphery, where it would be out of sight. Though the Catholic Church had explicitly forbidden the enslavement of Christians in Portugal’s Atlantic territories in 1435, there was no such prohibition against enslaving Africans. Thus, starting around 1450, the Portuguese monarchy, financed with Capital provided by bankers in Genoa, Venice, and Antwerp, began to build sugar production facilities on Madéira. They also purchased and imported hundreds of slaves each year from West Africa and the Canary Islands to work on Madéira’s roças. Though African slaves were said to be more “heat-tolerant,” the reality was they were simply the cheapest form of labor. And what grueling labor it was: felling trees, chopping and transporting firewood, clearing the land by digging and with fire, planting the cane, weeding the fields, harvesting the cane, transporting the cane, cutting and pressing the cane, feeding the boilers with firewood, cooking down the cane juice into sugar, and finally moving tons of sugar onto ships bound for Lisbon and other European ports.

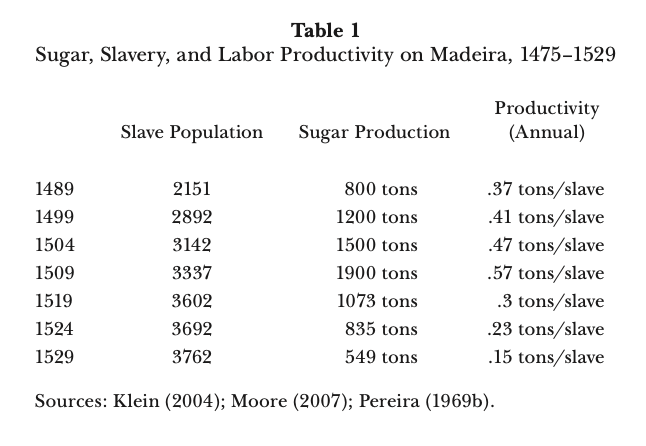

Table from geographer Jason Moore’s Madeira, Sugar, and the Conquest of Nature in the “First” Sixteenth Century (2010) illustrating how labor productivity emerged as the metric of value in the Capitalist world-system. Sugar production peaked on the island in 1509 before going into terminal decline and moving to neighboring Sao Tomas and eventually Brazil.

According to Binghamton University historical geographer Jason Moore, it was on the island of Madéira, that land, labor, and Capital became abstracted and commodified in a brand-new way, a way that would provide the template for the rapid growth of the Capitalist world-system. The capital investment for the roças was provided by backers who had no interest in developing the land outside of sugar production—like a commodity, Madéira was, for them, essentially an abstract space. The labor was not provided by European colonists or indentured servants that had to be treated like Christian persons, but by dislocated African slaves bought and sold as abstract commodities. “Ouro branco” (white gold) itself was almost the perfect commodity: a non-perishable, high value consumption good that was universally in demand, its grim origins invisible to consumers.

If it were possible to isolate world historical moments like the pilot test of Capitalism, a good candidate would be on Madéira in the year 1509. This is because 1509 was the year that labor productivity in Madéira’s sugar boom peaked. That year, 3,337 slaves produced 1900 tons of sugar, which is a labor productivity rate of .57 tons of sugar per slave, a rate never achieved on Madeira before or again. Thus it was in the roças that labor productivity emerged as the metric of value in the emerging world-system.

In his article Madeira, Sugar, and the Conquest of Nature in the “First” Sixteenth Century Moore writes, “This triple helix of commodification—sugar, land, and labor—explains the competitive dynamism of successive sugar revolutions across the early capitalist Atlantic, and with it, the rapid exhaustion of the local conditions necessary to sustain such dynamism.” Madéira’s ecological exhaustion slowly became apparent after 1509, as the Portuguese monarchy realized that no number of additional slaves could reverse the trend of declining labor productivity resulting from soil depletion and deforestation. (A staggering 160 kg of firewood was needed to produce a single kilo of sugar.) But once Madéira was used up, there was always São Tomé, and then Brazil, and then the Caribbean, and on and on and on. Portugal’s experiment established Capitalism’s perpetual cycle of boom, bust, and bail: to improve the rate of profit, the system was dependent on permanent global expansion to resolve the regional economic and ecological crises that it itself created.

Like a great white, the world-system has to keep moving, or perish.

10. The Beta Version

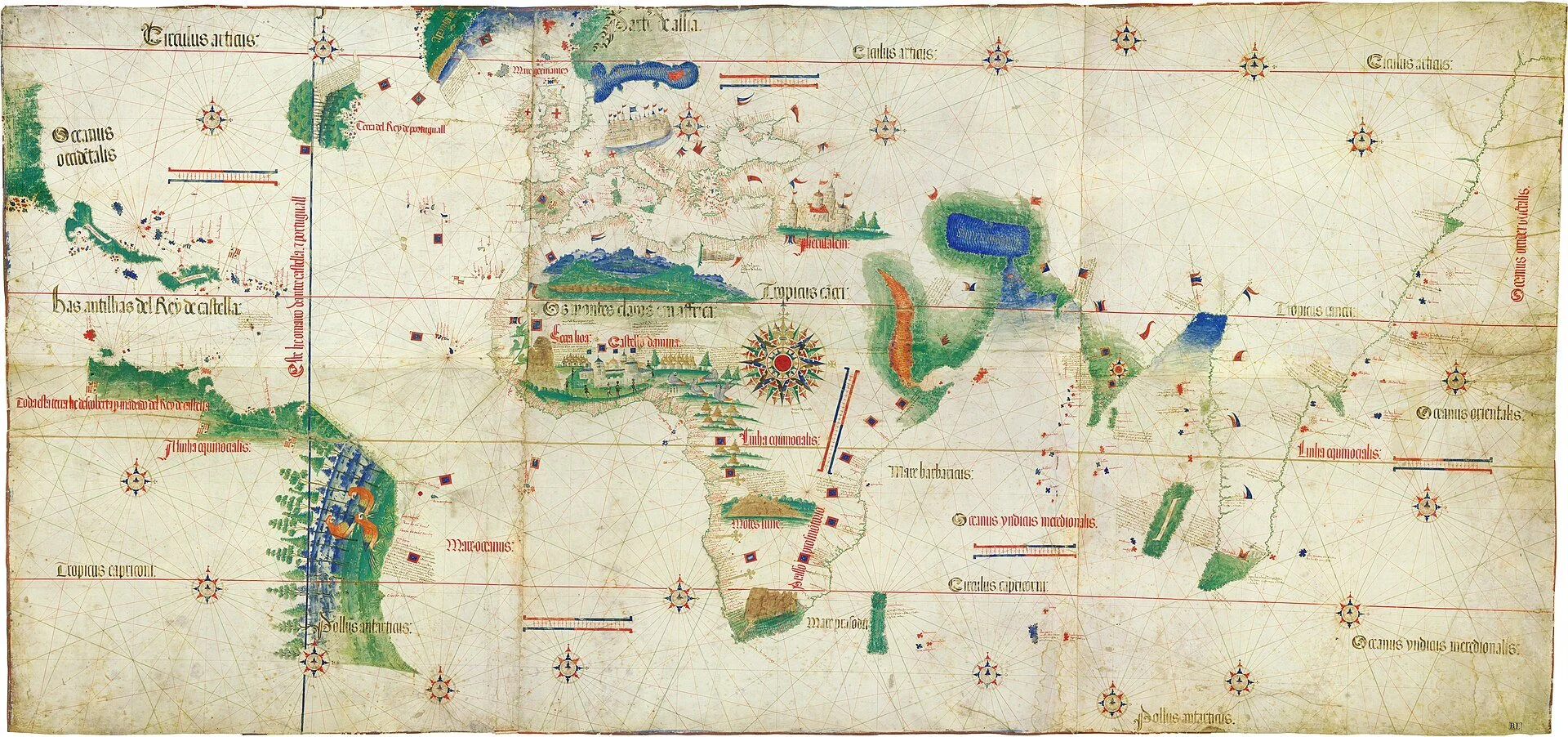

If Portugal can be said to have conducted the pilot test of the Capitalist world-system, then it was Spain who rolled out the beta version. In the early 1500s, Spain was still playing catch up with Portugal’s prodigious new expansion into the Atlantic, the coast of Africa, and the East Indies (India, Malaysia, and the Philippines). Columbus’ exploration and conquest of islands in the Caribbean had completely changed the game—so much so that following his “discovery” of the New World in 1492, Portugal and Spain, both intensely Catholic nations, clashed over claims to newly discovered territories. To resolve the dispute between his unruly offspring, Pope Alexander VI negotiated the Treaty of Tordesillas, which created an imaginary dividing line running through the Atlantic Ocean approximately 370 miles west of Cape Verde. The pope granted all newly discovered lands to the west of the line to Spain, and newly discovered lands to the east to Portugal. (Tough luck for the tens of millions of people already living there).

The Cantino Planisphere is the earliest existing map showing Africa, the eastern coast of Brazil, and part of the Indian subcontinent. The Treaty of Tordesillas meridian is the dark line running from north to south on the left side of the map.

The Treaty of Tordesillas is the reason why Magellan pitched an exploratory expedition to the Spice Islands to the west, and not via the eastern route that the Portuguese had already established. Magellan didn’t really have a choice.

Charles was determined to get a foothold in the lucrative spice trade, but did not have the cash needed to purchase and provision Magellan’s fleet. The unimaginable influx of gold and silver bullion from the defeat of the Aztec Empire would not reach Spain’s treasury for some time. Charles was already deeply in debt for a century-long series of wars on the Italian peninsula between the House of Hapsburg and Valois Kings of France—wars that had erupted before Charles’ birth and which would, more or less, be the death of him. Not only did he need money to pay for Magellan’s armada and the Hapsburg European war machine, Charles desperately needed cash to bribe the seven Catholic electors who could make him the next Holy Roman Emperor, a title he desperately wanted, as it would unite his holdings across Western Europe, creating a vast Hapsburg Empire.

Although liquidity was a constant problem for him, Charles had a line of credit with the man known as “God’s Banker,” Jakob the Rich, the head of the Fugger banking house of Augsburg, Germany, one of the wealthiest men who has ever lived, even by today’s standards. Fugger had grown obscenely wealthy providing high risk, high interest loans to spoiled European rulers. Decades earlier, Fugger had bribed the Catholic officials to elect Charles’ grandfather, Maximillian I, to the seat of Holy Roman Emperor, and he intended to pull the same strings for Charles.

Fugger loaned Charles two million florins (which seems like a lot of florins) to bribe the Catholic electors to crown him Holy Roman Emperor. Fugger also financed the Armada de Molucca, with additional funding from Castilian financier Cristóbal de Haro. All three of these men understood that a western expedition to the Spice Islands was a moonshot. But it paid off, they stood to make fortune.

This is how the world-system was stitched together.

11. A Million Dollars in Wine

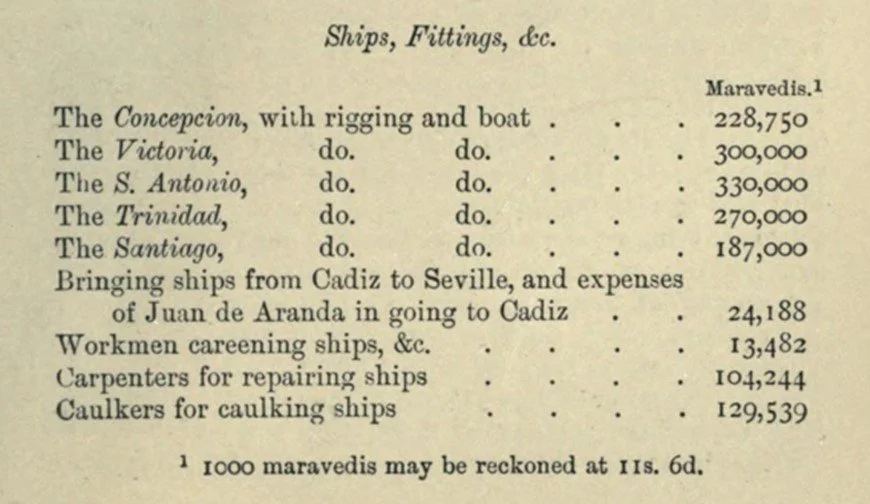

In the spring of 1519, five ships were commissioned for the for the Armada de Molucca: four massive, hundred ton carracks, the Concepción, San Antonio, Trinidad, and Victoria, and one smaller, more maneuverable seventy-five ton caravel, the Santiago. Extensive records show that provisioning the fleet cost nearly as much as the purchase of the ships themselves. In total, the expedition cost 8,751,125 maravedis—something on the order of ten million dollars today. Remarkably, the bulk of the food onboard consisted of two items: indestructible hardtack crackers and about 64,000 gallons of wine (508 butts of wine, to be exact). Thus, the first expedition around the world set out with almost a million dollars in wine.

The crews during the Age of Discovery were extremely diverse because of the experience required, the abysmal pay, and the steep mortality rate. Initially, Charles had wanted an all-Spanish crew. He was unable to recruit enough volunteers in Seville, however, leading to a crew made up of men from Portugal, North Africa, the Canary Islands, the Azores, Madeira, the Italian peninsula (your Venetians, your Genoese, your Sicilians, your Corfiots), and lesser numbers of French, German, Greek, Malaysian, and Flemish sailors, delightfully known as Flemings.

Three of the ships would never return to Spain: both Santiago and the Trinidad were shipwrecked, while the Concepción was burned and scuttled in the Philippines after becoming infested with shipworms and unseaworthy. The largest ship in the Armada de Molucca, the San Antonio, would ultimately desert the expedition, safely returning Spain with 55 mutineers in the spring of 1521, all of whom were acquitted of mutiny based on evidence of Magellan’s purported psychopathic behavior.

The only ship in the Armada de Molucca to complete the circumnavigation was the Victoria, which returned to Spain on September 6, 1522, captained by a Basque navigator named Juan Sebastián Elcano and carrying a crew of just seventeen haggard sailors. That’s about 7% of the men who set out.

12. Mutiny, Sodomy, and the Lash

I love to imagine Enrique on the deck of the Trinidad watching the crowds gathered below as the five hulking ships, covered in tar and pitch black, slowly sailed away from the docks at Sanlúcar de Barrameda on September 20, 1519. If he were ever to return home, this voyage would be his chance.

The ships briefly stopped in the Canary Islands to purchase pitch for caulking. While in Tenerife, Magellan received a secret message from his cousin, Diogo Barbosa, informing him the Spanish officers were planning a mutiny led by Juan de Cartagena, the captain of the San Antonio (who just happened to be Bishop Fonseca’s illegitimate son). Magellan was also informed that Manual I, the King of Portugal, had sent two fleets to follow the Armada de Molucca arrest him.

The first incident during the two month crossing was a sodomy trial for two crew members, Salomon Antón and António Varesa. Despite the fact that it was fairly commonplace among sailors, sodomy was still punishable by death in Spain. Eager to show Juan de Cartagena and any other potential mutineers what would be in store for them should they cross him, Magellan found Salomon Antón guilty of sodomy and sentenced him death, and when the fleet arrived in Brazil in December of 1519, Antón was strangled and his body burned. António Varesa was spared by Magellan, but was murdered by his shipmates a few months later after being thrown overboard.

The second serious incident came when tensions reached a head between Magellan and the captain of the San Antonio, Juan de Cartagena, Magellan’s main rival for control of the expedition. Magellan had already received information that Cartagena had been fomenting dissent by suggesting a mutiny to the other Spanish officers. After openly refusing to address Magellan by his proper title, Cartagena was summoned to Magellan’s ship, the Trinidad. Cartagena continued to mock Magellan in front the crew—right up until the moment Magellan had him arrested and put in stocks for insubordination.

It was a portentous start.

13. What Chance Might Offer

Over the centuries, tens of thousands of scholarly and popular books and articles about the expedition have been written. All of them to one degree or another rely on the same primary source, Antonio Pigafetta’s Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo, The First Voyage Around the World. While there are a few other firsthand accounts, such as the logbook of the pilot Francisco Albo, none come close to Pigafetta’s vivid, detailed portraits of encounters with indigenous people and the events of the voyage.

For the time period, Pigafetta writes like a proto-anthropologist, not just describing indigenous people’s appearance but attempting to understand their behavior in context or in terms of their environment. He makes ethnographic analogies to familiar parts of European life in order to highlight the underlying similarities of New World cultures which appeared radically different on the surface. In this passage, Pigafetta uses the palm tree to provide an extraordinary overview of the subsistence base of the Waray people of Suluan Island in the Philippines, a sort of early version of “follow the commodity” studies that are a common form of anthropological analysis:

Coconuts are the fruit of the palmtree. Just as we have bread, wine, oil, and milk, so those people get everything from those trees. They obtain wine in the following manner: they make a hole in the heart of the tree at the top called palmito, from which distills a liquor which resembles white must…The coconut is as large as a man’s head or thereabouts. Its outside husk is green and thicker than two fingers. Certain filaments are found in that husk, whence is made cord for binding together their boats…Under that shell there is a white marrowy substance one finger in thickness, which they eat fresh with meat and fish as we do bread; and it has a taste resembling the almond. It could be dried and made into bread. There is a clear, sweet water in the middle of that marrowy substance which is very refreshing. When that water stands for a while after having been collected, it congeals and becomes like an apple. When the natives wish to make oil, they take that coconut, and allow the marrowy substance to putrefy. Then they boil it and it becomes oil like butter. When they wish to make vinegar, they allow only the water to putrefy, and then place it in the sun and a vinegar results like white wine. We scraped the marrowy substance which we strained through a cloth, and so obtained milk like goat’s milk. A family of ten persons can support itself on two trees, by utilizing one for eight days and then the other for eight days for the wine; for if they did otherwise, the trees would dry up. By doing so they last a century.

Pigafetta’s travelogue contains some of the earliest ethnographic descriptions of the Tupí, Guaraní, and Tehuelche people of South America, the Chamorro people of the Mariana Islands, and the Cebu Islanders of the Philippines (not to mention, the first Italian-Tehuelche and Italian-Malay travel dictionaries). Pigafetta is often culturally clueless, but his interpretations are typically generous, if misguided. His book is first and foremost, however, a hagiography of Magellan, Conqueror of the Seas, primarily written for an audience of one: the King of Spain.

* * * *

After passing through heavy electrical storms and night skies illuminated by St. Elmo’s Fire, the fleet arrived finally off the coast of Brazil at the end of November, 1519, and stopped for repairs and reprovisioning near Rio de Janeiro in December. New lumber was brought aboard to replace the rotted and storm damaged parts of the ships. The water storage barrels were scoured and replenished. The ships’ stores were refilled with chicken, geese, fish, tapir, pork, sweet potatoes, cassava, pineapple, sugarcane, and other local foods. After months at sea coping with increasingly smaller rations of hard bread, wine, and questionable water, the crew were overjoyed by their new diet.

Unlike the expedition’s later interactions with indigenous people, the encounter with the local Tupí people was non-violent. The Spanish ships had appeared at the end of a long drought, which was interpreted by the Tupí as an auspicious sign. The Tupí were eager to trade food, supplies, and apparently sex, to obtain mirrors, knives, combs, bells, and other goods. One Magellan biographer hyperbolically described the two week visit as a “orgy of fornication and feasting and trade.”

In his travelogue, Pigafetta is more prosaic. “The men gave us one or two of their young daughters as [temporary sexual] slaves for one hatchet or one large knife, but they would not give us their wives in exchange for anything at all.” It’s hard to know how the “young daughters” felt about this exchange, but the according to Pigafetta, the Tupí were equally interested in the enigmatic Spanish men and their ships:

One day a beautiful young woman came to the flagship where I was, for no other purpose than to seek what chance might offer. While there and waiting, she cast her eyes on the master’s room and saw a nail longer than one’s finger. Picking it up most gracefully and gallantly, she thrust it through the lips of her vagina, and bending down low immediately departed.

Before leaving, Magellan held mass for the Tupí, who understood very little of what was being said. However, they were politic enough to kneel and pantomime the devotional gestures that seemed to placate this strange man and his priests.

The ships were repaired, the stores were full, the balls were empty, and the pagans ostensibly converted to Catholicism. It was time to move on.

* * * *

The Armada de Molucca departed Brazil the day after Christmas, 1519, and continued to travel south along the coast of what is now Uruguay and Argentina in search of a westward passage. During this time, Pigafetta recounts both friendly encounters and skirmishes with indigenous “giants” nearly twice the height of the crew, whom Magellan named the “Patagoni” due to their large feet. Several Patagonians were even brought aboard the ships as cultural ambassadors, but all of them died within months, presumably from European pathogens they had no resistance to.

On March 31st, 1520, Magellan halted the expedition at Port St. Julian in southern Argentina for the winter. Due to the extreme conditions, Enrique de Malacca and others became chronically ill. The men begged Magellan to turn back. But Magellan made it crystal clear that he would die before returning to Spain emptyhanded. Magellan implored them to be patient until the winter passed: gold, spices, and great wealth were waiting for them just on the other side of the passage (which, of course, wasn’t even remotely true).

But the cracks had already started to show.

14. April Fools!

On April 1st, Easter Sunday, Magellan ordered the crew ashore to attend Easter Mass, after which the captains were to dine at his table. Two of Magellan’s captains, Luis de Mendoza, captain of the Victoria, and Gaspar de Quesada, captain of the Concepción, refused to take part—a huge red flag.

That night at midnight Mendoza, Quesada, and thirty men with blackened faces quietly boarded the San Antonio and arrested its sleeping captain, Álvaro de Mezquita, killing any Magellan loyalists who dared resist. Once the mutineers had wrested control of the ship, they broke open the San Antonio’s stores and passed out food and wine to the famished crew to secure their support.

Magellan realized his control of the situation was rapidly deteriorating. The mutineers had captured three of his ships, the Concepción, the Victoria, and the San Antonio, leaving him outgunned. The mutineers had also sent a message: if Magellan capitulated to their demands and agreed to return to Spain, they would once again recognize his authority. The mutineers would only negotiate on board the San Antonio, however, for fear of violent reprisal.

But instead of sending his negotiators to the San Antonio, as the mutineers expected, Magellan sent a letter with his aguacil (a sort of constable) and five secretly armed men to the Victoria. Their arrival confused the mutineer captain of the Victoria, Luis de Mendoza—this wasn’t part of the plan. Magellan’s aguacil solemnly presented the letter to Mendoza, which summoned him to the Trinidad to face Magellan.

The letter, however, was nothing more than misdirection.

Because as Mendoza began to read it aloud, Magellan’s aguacil leapt forward and stabbed him in the throat with a dagger. When Mendoza dropped dead on the deck, Magellan’s men drew their hidden weapons. In the commotion, more of Magellan’s reinforcements were also able to board. The shock of Mendoza’s gruesome, unexpected assassination had served its purpose, and the mutineers quickly surrendered.

With the Victoria once again under his command, Magellan maneuvered his ships to block the harbor. Similar to his earlier ruse, Magellan used his canons to create a cacophony, and in the midst of this distraction was able to get his loyalists aboard both the San Antonio and the Concepción, where they the remaining mutineer captains, Gaspar de Quesada and Juan de Cartagena. They could see that Magellan’s reclamation of authority was total, a fait accompli. It would be a miracle if he let any of them live.

* * * *

Surprisingly, however, the majority of the mutineers were spared death. The ringleaders, however, were not so lucky.

Magellan was determined to use the situation to consolidate his power. He immediately court-martialed Luis de Mendoza, who was found guilty and then hanged, drawn, and quartered right there on the deck of the ship, his body parts spitted on poles as an example to the rest of the crew. Forty of the mutineers were found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. But after making them sweat for a while, Magellan granted them clemency, largely because it would have been impossible to continue otherwise. Their sentence was “reduced” to being kept in chains in the bowels of the ships to run the bilge pumps in fetid darkness.

The mutineer captain Gaspar de Quesada agreed to be beheaded by his servant—which was considered a more merciful death than being marooned—on the condition that his servant be given clemency for performing the ugly task. Afterwards, Quesadsa’s body was left in a gibbet that was found sixty years later by Sir Francis Drake, the first Englishman to circumnavigate the Earth.

Magellan had turned a disaster to his advantage. He was able to replace the mutineer captains with loyalists, and was now in an even stronger position than prior to the mutiny. A few weeks later, the Santiago shipwrecked while on a long-distance reprovisioning mission. Magellan understood the men’s misgiving abouts his brutality during the Easter Mutiny, and thus he made a great effort to rescue the survivors of the Santiago. After much derring-do, a search party was eventually able to locate the survivors, and miraculously, all 37 men aboard the Santiago were saved.

The final mutineer to be dealt with before the expedition continued south was Juan de Cartagena, who had been the first man to challenge Magellan’s authority so many months before. Cartagena was abandoned with an “abundance of wine and bread” on a small, cold island off the coast of Patagonia.

* * * *

When the winter was over, the fleet departed Port St. Julien and sailed south, continuing to search for a passage leading to the west. Finally, on October 21st, 1520, after investigating what appeared to be another in an endless series of inlets, Magellan found the long awaited passage. As Pigafetta recalls in his travelogue, “We all believed it was a cul-de-sac; but the captain knew that he had to navigate through a very well-concealed strait, having seen it on a chart preserved in the treasury of the King of Portugal, and made by Martin of Bohemia.” The truth to Pigafetta’s assertion is a bit murky, but Magellan’s original pitch to Charles had been to go west “in search of the strait” and he had delivered, however it was accomplished.

As the Trinidad, Concepción, and Victoria entered the strait, the fleet lost sight of the San Antonio, which seemed to simply vanish. Magellan’s assumption was that the San Antonio had shipwrecked on hidden shoals in the strait, in the same manner as the Santiago weeks earlier. Given that a third of the food and provisions were stored onboard the San Antonio, its disappearance was a complete disaster. Of course, Magellan would not live to find out the truth of the matter, that San Antonio had deserted the expedition and returned to Spain.

* * * *

The landscape on either side of the strait grew truly strange and scary, but Magellan was undaunted. He had come to view his own choices through the lens of divine providence. Pigafetta writes that the banks of the strait were “as narrow as a gunshot” in places, leaving the crew nervous that an ambush could come at any moment. The expedition spent 38 eerie days travelling through the 300 mile passage. Seeing the hundreds of fires built by native people along the banks and far off in the distant darkness, Magellan named the land Tierra del Fuego (Land of Fire).

When the fleet finally exited the strait into a calm, tranquil sea, Magellan coined yet another name for a geographic body that stuck, the Mar Pacifico or Pacific Ocean. Now completely off the map, the expedition sailed north along the coast of Chile. Magellan pleaded with the crew to be patient: by his estimate, the Spice Islands were probably no more than 600 miles due west. They were “so close,” in fact, that Magellan elected not to stop to reprovision the ships and secure potable water before heading out into the open ocean. It was a colossal mistake.

15. A Three Hour Tour, A Three Hour Tour

No one on board had a clue as to the sheer vastness of the Pacific Ocean. In reality, the ships had not set off on a 600 mile voyage, but a 10,000 mile slog across the Pacific, a journey that would take them almost four months.

The days trickled by as the crew gradually moved from being bored to death to being malnourished to death. There were few diversions. Sailors could whittle, pray, or sing accompanied by drums, tambourines, or other instruments, or perhaps play dice or card games. Sex was clearly off the table. According to Pigafetta, the men survived the ordeal by drinking putrid yellow water and eating anything they could:

We ate biscuit, but in truth it was biscuit no longer, but a powder full of worms, for the worms had devoured its whole substance, and in addition it was stinking with the urine of rats. So great was the want of food that we were forced to eat the hides with which the main yard was covered to prevent the chaffing against the rigging. These hides, exposed to the sun and rain and wind, had become so hard, that we were obliged first to soften them by putting them overboard for four or five days, after which we put them on the embers and ate them thus. We had also to make use of sawdust as food, and rats become such a delicacy that we paid half a ducat a piece for them.

A true example of the free market at work.

Over the next four months, nineteen crew members died. But the primary cause of death was not starvation, but scurvy, a mysterious illness that killed millions upon millions of sailors during the first two centuries of the Age of Discovery, until it was discovered to be a vitamin C deficiency in the world’s first randomized control trial in 1747. Scurvy lead to an agonizing death that caused sailors teeth to fall out, followed by weakness, bleeding, and finally convulsions.

Differences in social class aboard the ships can be seen in in the epidemiology of the scurvy outbreak during the Pacific Crossing. While the crew was decimated by the disease, Magellan, Pigafetta, and the other officers did not suffer from the mysterious malady, likely because they were eating Carne de membrillo (preserved quince fruit), a delicacy that happened to contain vitamin C. Pigafetta in fact notes in his travelogue that he was surprised by his own good health as compared to the illness of the rest of the crew.

Accounting for various mutineers, maroons, and mortalities, there were now half as many men as when the expedition started.

* * * *

On March 6, 1521, the fleet finally spotted land: the island of Guåhan, or Guam, which 500 years later is still a territory of a core country in the Capitalist world-system. Overjoyed at the prospect of fresh water and food, the crew watched as outrigger canoes filled with Chamorro men paddled out to greet them. Groups of the islanders clambered aboard and swept through the ships, fascinated with the ships and the European’s strange objects.

Soon this good natured curiosity turned into what the Spaniards saw as theft, as the Chamorro clambered through the decks and fled with everything they could carry, also taking with them Magellan’s bergantina (a small transport boat). For the Chamorro, whose economy was largely reciprocal and redistributive, and the concept of private property was a bit alien. Most material goods among the Chamorro circulated in a web of gift-giving, which served to maintain social cohesion and build relationships. To the Chamorro, the chance meeting with the Spanish was probably seen as a bonanza of relationship-building with a powerful new ally who could give the Chamorro access to fantastic, completely unheard of trade goods.

Perhaps the men were weak from scurvy and malnutrition, or perhaps they were merely dumbfounded and outnumbered. Whatever the case, the Chamorro clearly did not understand the capacity of these white men with scraggily black beards to remain passive moments before committing mass murder without warning.

After the “robbery,” Pigafetta writes, “the captain general in wrath went ashore with forty armed men, and they burned some forty or fifty houses together with many boats, killed seven men, and recovered the small boat.” Magellan ordered him men to burn down the Chamorro village, and the fleet quickly departed the so-called “Island of Thieves.” The ships were followed by angry, distraught Chamorro women in canoes, wailing, pulling at their hair, and throwing rocks at the fleeing ships.

Perhaps one of their curses stuck. Magellan’s slaughter at the Chamorro village in March of 1521 foreshadowed the events leading up to his death in the following weeks.

16. Beware the Ides of March

When the Armada de Molucca landed a few days later on the island of Limasawa in the Philippines, Enrique de Malacca was able to understand the local language for the first time. When he spoke, Pigafetta writes, “They immediately understood him.”

Magellan was elated. Enrique’s ability to speak with the Limasawa islanders was proof that the expedition had found a western route around the world after all—they were back on the map, baby. Although Magellan himself clearly thought that Enrique was from Malacca in Malaysia, some historians suggest that Enrique’s fluency suggests he was a native Cebuano speaker from the Philippines. In their view, this is proof that Enrique had already completed a “linguistic circumnavigation” by this point.

* * * *

When the Spanish were informed of gold prospecting in the area, and saw the gold finery of the local kings, Magellan decided it would be a good place to make strategic partnerships on behalf of Spain. His priests held the first Catholic masses in the Philippines, baptizing thousands of islanders, followed by feasts at which the men ate and drank themselves unconscious. In a rare moment of cultural relativism, Magellan sealed the deal by making traditional Philippine blood compacts with Rajah Kolambu, King of Limasawa, and Rajah Humabon, King of neighboring Cebu. Humabon happily converted to Catholicism when presented with a Spanish suit of armor, and made promises of payments of gold tribute for the King of Spain, which was notarized by the expedition’s notary, of course.

Magellan’s quick and painless success, however, led him to expect nothing less than complete acquiescence from all local people. After the Spanish ordered the islanders to burn their religious effigies (referred to as “idols” by the Spanish), Magellan became incensed when he learned that some households had hidden their “pagan” paraphernalia to save it from the auto-da-fé.

Rajah Kolambu and Humabon started to realize that the strange presence of the Spanish was not a limited hang. If Magellan was not stopped, Kolambu, Humabon, and indeed all of the chiefs, would eventually be robbed of their sovereignty. The domination of the Spanish, with their canons and crossbows and crosses, would never end.

Humabon informed Magellan that Lapu-Lapu, a recalcitrant chief on the neighboring island of Mactan, had refused to convert to Catholicism or pay tribute to the King of Spain. When Humabon asked Magellan to join in a retaliatory attack on Lapu-Lapu’s village on the neighboring island of Mactan, Magellan, against his officers’ advice, accepted the challenge immediately. This is speculation on my part, but from the outside it seems like the perfect setup for Rajah Humabon to eliminate or weaken two of his adversaries by pitting them against each other. Humabon may not have had canons, but he did have home field advantage.

Now at peak megalomania, Magellan believed that divine providence and Spanish weapons and armor simply would not fail him. As a show of Spain’s military supremacy, Magellan insisted on sending a relatively small landing party the next morning comprised only of Spanish soldiers. Humabon’s warriors, who were no doubt much more familiar with Lapu-Lapu’s strengths and tactics, had been sidelined. They were instructed to wait in boats offshore and watch Magellan trounce this pagan troublemaker.

17. Dog Catches Car

“The Captain desired to fight on Saturday, because it was the day especially holy to him.”

“When morning came forty-nine of us leaped into the water up to our thighs, and walked through water for more than two crossbow flights before we could reach the shore…When they saw us, they charged down upon us with exceeding loud cries, two divisions on our flanks and the other on our front.”

Magellan’s first problem was getting Lapu-Lapu’s warriors to stand still long enough for the Spanish musketeers and crossbowmen to hit them. During the night, Lapu-Lapu had prepared hidden defensive structures on the beach. His lighter, more mobile fighters were able to move across the wet sand more easily, and they rained down arrows and iron-tipped bamboo spears on the Spaniards with impunity.

Magellan had failed to stick the landing.

He could also see they were outnumbered. Overwhelmed, he ordered Pigafetta to take a few of the men to the nearby village and “Burn their houses in order to terrify them,” the same tactic Magellan had used against the Chamorro. This act of terrorism and destruction directed at innocent people enraged Lapu-Lapu, who had cautiously waited to deploy most of his men. Pigafetta later estimated that some 1500 warriors descended on the Spanish landing party on the beach.

Hearing the battle, the ships fired off their canons, but were too far away to effectively hit anything. Fighting in water up to his knees, Magellan was shot in the leg with a poison arrow, and ordered his men to retreat. This was the end.

Recognizing the captain, so many turned upon him that they knocked his helmet off his head twice, but he always stood firmly like a good knight. Together with some others, we fought thus for more than one hour, refusing to retreat farther. An Indian hurled a bamboo spear into the captain’s face, but the latter immediately killed him with his lance, which he left in the Indian’s body. Then, trying to lay hand on his sword, he could draw it out but halfway, because he had been wounded in the arm with a bamboo spear. When the natives saw that, they all hurled themselves upon him. One of them wounded him on the left leg with a large terciado, which resembles a scimitar, only being larger. That caused the captain to fall face downward, when immediately they rushed upon him with iron and bamboo spears and with their cutlasses until they killed our mirror, our light, our comfort, and our true guide.

Ironically, Magellan could have easily fielded a much larger landing force by combing Humabon’s men and the rest of the Spanish soldiers, or used his canons more effectively during the attack, but hubris simply got the better of him. Later, when Enrique de Malacca sent a message to Lapu-Lapu stating that the Spanish would pay basically anything in exchange for Magellan’s body, Lapu-Lapu replied that “They would not give him up for all the riches in the world, but that they intended to keep him as a memorial.”

And true to his word, Lapu-Lapu kept Magellan’s body as a memorial, and no doubt as a warning.

The Lapu-Lapu Monument on Mactan Island, which commemorates his victory over the Spanish in 1521, depicts a fully-imagined and totally-ripped Lapu-Lapu holding traditional Kampilan sword and shield (Photo by Aisaka Taiga)

Lapu-Lapu’s resistance delayed Spanish colonization for another half century. Today there are statues of him on Mactan and elsewhere in Philippines, where he is regarded as a hero who, much like Enrique de Malacca, serves as a tacit rejection of European Colonialism. It is fitting that Lapu-Lapu’s image is the official symbol of the Philippine National Police.

18. Fuck Around and Find Out

Enrique de Malacca, who was injured in the Battle of Mactan, had served loyally as Magellan’s body-man throughout countless battles and hardships, risking his life literally dozens of times for him. Magellan, for his part, viewed Enrique almost as a son. Enrique’s disillusionment with the leaders of the expedition seems to have resulted from the reading of Magellan’s will, which stated

I declare and ordain as free and quit of every obligation of captivity, subjection, and slavery, my captured slave Enrique, mulatto, native of the city of Malacca, of the age of twenty-six years more or less, that from the day of my death thenceforward for ever the said Enrique may be free and manumitted, and quit, exempt, and relieved of every obligation of slavery and subjection, that he may act as he desires and thinks fit; and I desire that of my estate there may be given to the said Enrique the sum of ten thousand maravedis in money for his support; and this manumission I grant because he is a Christian, and that he may pray to God for my soul.

After the Battle of Mactan, the newly elected captains, Duarte Barbosa and João Serrão, ordered Enrique to return to shore to negotiate with local leaders—Enrique, after all, was the only person that could communicate in Cebuano. Recovering from his injuries, Enrique refused to get out his bed. According to Pigafetta, the captains flew into a rage, and castigated Enrique that was he was still a slave and would return to Spain as a slave. He would be flogged immediately if he continued to disobey.

I can only imagine the betrayal that Enrique must have felt after serving Magellan his entire adult life, only to have his legitimate chance for freedom stolen from him. Perhaps it was at this moment that Enrique finally said Nah son and began to hatch a plan to escape or to seek retribution on the Spaniards that threatened his life and those of everyone else they encountered.

Enrique had no choice but to follow the captains’ orders and return to Cebu to ask Humabon for help in negotiating a peace settlement. Enrique and Humabon made plans to throw a banquet for the remaining Spanish officers where they would be compensated for Magellan’s “wrongful death” with gifts of jewels gathered from local leaders.

There is no way of knowing if Enrique conspired with Humabon to ambush the Spanish delegation, as Pigafetta later surmised. But in retrospect the invitation to the lavish banquet on Cebu—designed to both lionize the Spanish officers and cater to their craving for gold and gemstones—seems like an obvious setup, too good to be true. And the Spanish took the bait.

Four days later, Enrique, along with captain João Serrão, and a landing party of about twenty-four Spanish officers landed on Cebu to attend the peace negotiation and banquet. At some point during the meal, Humabon’s warriors abruptly stormed in and massacred the party of Spaniards. Pigafetta, who was on the ship recovering from an arrow wound to the face wrote that much screaming from the massacre of the Spanish officers could be heard in the distance. The ships began to discharge their canons into the village.

Pigafetta writes, “While thus discharging [the canons] we saw João Serrão in his shirt bound and wounded, crying to us not to fire any more for the natives would kill him. We asked him whether all the others and the interpreter were dead. He said that they were all dead except the interpreter.”

All dead, except the interpreter.

From the beach, Serrão begged the crew to ransom him from the islanders. But the crew had had enough of the officers’ abysmal leadership, which had completely failed to get them to the Spice Islands and nearly killed everyone. As the ships sailed away without him, Pigafetta could still hear Serrão weeping and cursing at them from the beach to rescue him.

In terms of world historical revenge stories, it’s pretty epic.

* * * *

After May of 1521, Enrique de Malacca disappears from the historical record.

If, like historian Federico Magdalena, you see Enrique’s fluency in Cebuano as proof that he was a native of the Philippines, then by this point, Enrique had already circumnavigated the globe, beating Elcano and the Victoria by a good 15 months.

If you instead accept Magellan’s assertion that Enrique was from the port of Malacca or a neighboring area, then he would still have had to travel another 1650 miles southwest to fully circumnavigate the Earth. Given the fact that Enrique was a young, seasoned, multilingual sailor who had already come some 23,300 miles (93.3%) around the Earth, he could have very comfortably arrived before the Victoria returned to Spain the following year.

* * * *

There is a rather satisfying irony to the idea that the first person to circumnavigate the Earth was an enslaved slave boy from the periphery, who never set out to travel around the world in the first place, rather than the psychotic emissary of a world-eating empire who did.

19. Twilight in the Empire on which the Sun Never Sets

Charles, born into a feudal world, ultimately failed in his quest to become World Hegemon, and Spain did not become the center of the emerging Capitalist world-system. But it wasn’t for a lack of trying. In the decade between 1530 and 1540, Charles came to govern half of the population of the Western Hemisphere. The volume of transatlantic trade increased by ten times during his reign. But by 1557, the dream was over.

Charles suffered from a malady that has afflicted kings and oligarchs across time and space and which ravages the world to this day: a terminal, toxic addiction to more. More power. More property. More wars. More subjects. More money. More titles.

Ultimately it was more debt that became his undoing. The flood of gold and silver bullion from Spain’s New World colonies, obtained though the enslavement and genocide of the Aztec, Inca, and other indigenous groups, was almost unimaginable. But unexpectedly, this unprecedented influx of hard currency created dramatic, uncontrollable inflation across Spain. It also caused Charles to begin borrowing greater and greater sums of money at an unprecedented rate. Instead of responding to this debt crisis responsibly, Charles’ creditors, with dollars signs in their eyes, became blind to the risk of becoming overleveraged. No one wants to say no to the King.

The money that poured in from Spain’s colonies was primarily sent straight to Augsburg to repay the Fuggers, or to creditors in Antwerp and Venice and Genoa, rather than being invested in strengthening or professionalizing the paper-thin bureaucracy that administrated Spain’s territories, or to private financial institutions or merchant fleets—Capital investments that might have held Spain’s far-flung empire together. Instead, the profits increasingly went to service the interest on Charles’ preexisting debt.

Exhausted, Charles abdicated in 1556 and the Spanish Empire, under crushing debt, fell into bankruptcy, wiping out the fortunes of the Fuggers and many other European banking families with it. His empire fell apart before becoming the first core of the world-system, an honor generally accorded to the Dutch Republic and the East India Company in the early 1600s, which continued the work of primitive accumulation and establishing a global division of labor. A tale for another day.

20. We are in a Closed Loop

In many ways, the violent and chaotic 21st Century is a lot like the violent and chaotic 16th Century. Like Charles, we can see the social and economic system we were born into dying in front of our eyes, but we can’t yet quite make out the system that will replace it. In the short term, it seems unlikely that the United States will remain at the center of the world-system, as the core shifts westward towards China and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, and away from the United States’ financialized, debt-ridden, postindustrial Pay For The Printer future.

Wallerstein predicted that the Capitalist world-system would die about halfway through the 21st century, after its internal contradictions lead to a structural crisis that the world-system cannot survive, what he termed a “bifurcation” or the emergence of two possibilities, two alternative outcomes. I think we are living in this bifurcation right now, and we have been since the American government’s frenzied and ultimately disastrous imperial response to the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001, a response that in hindsight looks increasingly overdetermined.

The symptoms of the structural crisis have been clear for at least the past two decades (although Wallerstein started publishing his work on the instability and potential collapse of the Capitalist world-system in the 1970s). The 21st century opened with the greatest difference between rich and poor in history, a gap now so vast it is hard to grasp. Attempts to resolve regional economic crises through global expansion no longer work, and the finite nature of the world confronts us more each day. Wars in hot spots around the world smolder for years or decades, but are never extinguished—the last bit of juice to be had is in the conflict, not the resolution. Speculative tech and real estate bubbles grow out of control, but don’t generate value or employment, resulting in more frequent crashes and recessions that governments and central banks struggle to contain. The US is now in more debt than any entity in world history, and will soon spend more to service its debt than on its military—historically a sign of an empire in terminal decline. (In 2024, the US spent about $880 billion on interest for its debt and about $886 billion on its defense budget.) Recent data demonstrates that efforts to reignite Capitalism have stalled, and suggest the TRPF is indeed real, despite the furious cries of Neoliberal economists to the contrary (the lady doth protest too much, methinks). To quote historian Matt Christman, “There really is no other place on Earth that is not part of the global Capitalist market. So there’s no more frontier to find new sources of exploitation, new sources of margin, of profit. We are in a closed loop.”

There’s no denying that interregnums or bifurcations, or whatever you want to call them, are scary periods full of anxiety and uncertainty. But this chaos also gives rise to opportunities, world historical moments in which the mass of ordinary people are able to make effective changes and mold a successor system in which new social conditions are possible—the weeks in which decades happen, as it were. Wallerstein, who died in 2019, believed there were two possible outcomes that can result from the current, ongoing structural crisis of Capitalism: there is a 50% chance that a more authoritarian, hierarchical, ecologically destructive society will dominate the future, and a 50% chance that a more democratic, egalitarian, sustainable society will emerge.

Considering where we are right now, those look like pretty good odds to me.

Postscript: Time and Distance Overcome

When the Victoria finally reached the Canary Islands on its return voyage to Spain on July 9th, 1522, Pigafetta writes,

“We charged our men when they went ashore in the boat to ask what day it was, and they told us that it was Thursday for the Portuguese. We were greatly surprised for it was Wednesday for us, and we could not see how we had made a mistake; for as I had always been healthy, I had set down every day without any interruption. However, as was told to us later, it was no error, but as the voyage had been made continually toward the west and we had returned to the same place as does the sun, we had made that gain of twenty-four hours, as is clearly seen.”

The crew of the Victoria had arrived at tomorrow today.

* * * *

Three years later, in 1525, two veterans of the first circumnavigation, Juan Sebastián Elcano and Hans von Aachen, set out on a second voyage around the Earth. Elcano died from scurvy the following year while crossing the Pacific. But in 1534, after some nine years of travelling, Hans von Aachen returned to Europe and became the first person to circumnavigate the world twice.

The process of pulling the entire world into Capital was gradually, then suddenly, picking up speed.

Resources and Further Reading

Lawrence Bergreen, Over the Edge of the World: Magellan's Terrifying Circumnavigation of the Globe (Perennial 2004).

Rommel A. Curaminga, Historical versus Practical Pasts? Enrique de Malacca in Malaysia’s Historical Imagination (Hist. Historiogr., Ouro Preto, Vol. 16, 41: 1-22, 2023).

Minqi Li, Endless Accumulation: Limits to Growth, and the Tendency for the Rate of Profit to Fall (World Review of Political Economy Vol. 7, 2:162-181, 2016).

Federico V. Magdalena, Who Is Enrique De Malacca In Philippine History? (Filipino Chronical 2023).

2023. Enrique de Malacca: Malay or Cebuano? (Tugkad: A Literary and Cultural Studies Journal, 2023).

Marx, Karl, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume III: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole (edited by Friedrich Engels, 1894, Marxists.org, 1999).

Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (Penguin Books 1985).

Jason W. Moore, Madeira, Sugar, and the Conquest of Nature in the "First" Sixteenth Century: Part I: From "Island of Timber" to Sugar Revolution, 1420–1506 (Fernand Braudel Center Review, Vol. 32,4: 345-390, 2009).

Jason W. Moore, Madeira, Sugar, and the Conquest of Nature in the “First” Sixteenth Century, Part II: From Regional Crisis to Commodity Frontier, 1506–1530 (Fernand Braudel Center Review, Vol. 33,1: 1–24, 2010).

Antonio Pigafetta, The First Voyage Around the World (1519-1522): An Account of Magellan’s Expedition. (Ed. Theodore J. Cachey Jr., Marsilio, 1995).

Tomas N. Rotta and Rishabh Kumar, Was Marx right? Development and exploitation in 43 countries, 2000–2014 (Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 69, 213-223, 2024).

Reni Roxas and Marc Singer, First Around the Globe: The Story of Enrique (Ilaw ng Tahanan Publishing, 2017).

John Sailors, http://www.enriqueofmalacca.com/p/enrique-of-malaccas-origin.html

Lord Stanley of Alderley, Voyage Round the World by Magellan: Translated from the Accounts of Pigafetta, and Other Contemporary Writers, Accompanied by Original Documents (The Hakluyt Society London, 1874).

Immanuel Wallerstein: The Rise and Future Demise of the World Capitalist System: Concepts for Comparative Analysis (Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 16, 4: 387-415, 1974).

2004. World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction (Duke University Press 2004).

2011. The Modern World-System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century (University of California Press 2011).

2011. The Modern World System II: Mercantilism and the Consolidation of the European World-Economy 1600—1750 (University of California Press 2011).

2015. The Modern World-System as a Capitalist World-Economy (The Globalization Reader, Wiley & Sons Ltd.)

Footnote [1]: