Who’s Afraid of Sally Binford?

Life After Anthropology

I. The New Archaeologists

On a winter day at the end of January, 1994, just shy of her 70th birthday, Sally Rosen Binford cleaned her house and carefully arranged her things. She wouldn’t be needing them, but she wanted to convey a sense of orderliness, of intention — a visual sign of someone in control, with their faculties intact. Rosen Binford had put her legal affairs in order and mailed farewell letters explaining her intentions to friends, family, and lovers around the San Francisco Bay area. When everything was squared away, Sally proceeded to carefully feed a handful of pills to her companion, a geriatric poodle named Jake, and then to herself. They both died on the spot.

While the name Sally Binford means little to most people, saying the name “Binford” to an anthropologist or an archaeologist is its own kind of dog whistle. That’s because in the late 1960’s, Sally and Lewis Binford, her then-husband and colleague at the University of Chicago, were two key proponents of a radical paradigm shift in archaeology. In a series of articles and a book entitled New Perspectives in Archaeology, the Binfords were a driving force behind a movement known as “The New Archaeology.”

The Binfords weren’t the first New Archaeologists, but they were probably the loudest. The New Archaeology was essentially the scientification of archaeology, moving the discipline away from history and art history and towards the application of complicated scientific techniques and savvy statistical analyses. Going forward archaeologists would emulate the hard sciences (biology, chemistry, and physics): they would make hypotheses, test the data for statistically significant patterns, and draw their conclusions from scientific evidence rather than from “just so stories.” Archaeologists were not gun-toting, tomb-raiding antiquarians wearing fedoras and leather jackets; they were pipette-toting, Excel-raiding technicians wearing lab coats and latex gloves. The New Archaeology became foundational to how archaeological lab work and excavations are conducted all over the world to this day, and Lewis Binford went on to become one of the most acclaimed and notorious of its practitioners in the 20th century (very few archaeologists can say they had six wives, were elected to the National Academy of Sciences, and had an asteroid named after them).

But this isn’t a story just about anthropology; it’s a story about life after anthropology. It’s one version of the life of Sally Rosen Binford, who was also a brilliant archaeologist, but who sought those intangible things we sometimes seek in anthropology: an unfathomably deep but fleeting human experience, a cultural moment you can grasp but never quite hold onto. It’s the story of a person who, rather than be paralyzed by ineffectual academic formalism, chose activism and to stand up for what is right (even if “what is right” can’t always be agreed upon). Sally defied categorization: in addition to her role as a pioneering female archaeologist, she was also advocate for feminist Americans, African Americans, Native Americans, elderly Americans, LGBTQ Americans, Jewish Americans, and otherwise disenfranchised Americans, just to name a few. This is also a story about the variations of love, which is never really knowable and certainly not falsifiable, and thus a far more intriguing topic than science to me.

II. Troublemaker

Sally Rosen Binford’s life is much rumored but little written about, with a few notable exceptions. This essay could not have been written without Liz M. Quinlan’s excellent academic conference paper ‘…and his wife, Sally’: The Binford Legacy and Uncredited Work in Archaeology” (2019). The bulk of this essay however is drawn from Sally’s own words from a long-form interview published in Janet Clinger’s book Our Elders: Six Bay Area Life Stories (2005). This interview is a striking combination of erudition and candor, and ultimately a morality tale about how to live your life without compromising your values. It’s safe to say Sally was a searcher.

Sally Rosen was born in Brooklyn in 1924 to leftist parents who became more and more conservative as they grew older. “I was supposed to be a Jewish princess, but something went wrong.” Her introduction to complicated racial dynamics came early. “When I was in the second grade in public school in Brooklyn, this little boy and I had a real crush on each other. When the teacher came to dinner at our house, I remember hearing her and my parents laughing, their being so amused and snotty about it, because this little boy, whom I had a crush on, was Chinese…My sister told me that Chinese are dirty and steal and carry knives and murder kids — all kinds of nonsense.” The irony of these attitudes towards minorities despite the fact that the family was Jewish was not lost on her.

Growing up during the rise of fascism in Europe gave Rosen Binford a keen awareness of her identity. “During the thirties, when I was a kid, my parents were enraged about racism in Germany and then they would sit around and talk about “schwartzes” [Yiddish slang for African Americans]. When I was a teenager, thirteen or fourteen, I said, ‘Don’t you see any inconsistency there?” This contradiction made her furious. Her sister was favored by her parents, while Sally was considered the troublemaker. “My sister is close to my age and was exposed to exactly the same thing and yet we are just as different as day and night — I have a very low tolerance for bullshit and lies.”

In 1941, Sally was kicked out of the USO. “I had a big fight with my parents about the incarceration of the Japanese in 1941. I was seventeen when that happened. I was a junior hostess at the local USO and I danced with a black sailor. I was expelled because ‘We don’t dance with black sailors.’ I said, ‘Why not?’ She said, ‘Because we don’t!’” Rosen Binford longed to get out of New York City and away from her family.

III. Escape from New York

She fled to Vassar College, eclipsing her sister and fulfilling her mother’s Ivy League ambitions, but was unhappy there. “I don’t know what my expectations of college were, but Vassar did not meet them. The classes were disappointing, and the women were extremely snobbish.” By spring vacation she had decided not to return. When her parents withdrew their financial support, Rosen Binford took it as an opportunity to broaden her world. In the mid-1940’s, she worked writing case histories in a psychiatric clinic in New York. She started hanging out in Greenwich Village, dating jazz musicians, and experimenting with drugs. “For an overprotected Jewish princess, it was quite an eye opener.”

In 1945, Sally was accepted to the University of Chicago. Momentarily back in the good graces of her parents, her father’s racism was again a problem when she decided to move to the South Side of Chicago from Greenwich Village. When her father visited her at the University of Chicago, he asked how she could stand to live surrounded by “communists, faggots, and niggers.” Rosen Binford replied, “I like communists, faggots, and niggers.”

Sally thrived at Chicago: she was finally in her element. She had a baby, Susan, with a graduate student whom she married in 1947. She loved both being pregnant and being a mother — much more so than being a wife, she quickly realized. “Toward the terminal stages of the marriage he said to me, ‘You didn’t want a husband, you just wanted the egg fertilized.’ I became totally outraged and thought what a son-of-a-bitch to say that. Then I thought about it for a while and said, ‘You are totally right. I really didn’t want a husband. I just wanted a baby.’”

When Sally told her parents she was getting divorced, they were furious and again withdrew their financial support. A full-time mom for the first time, she had to think on her feet. “The first year I was separated was the most maturing year of my life. I was 26 and had never been totally on my own. I had always had my parental support and then my husband’s.” Newly single, she was shunned by the circle of married women around her, spending a long, lonely year trying to sort her life out. It was a shock to the system.

Eventually things improved. The post-war dating scene in the Hyde Park area near the University of Chicago involved a tremendous amount of romantic reshuffling and switcheroos. “Everybody was dating everybody’s ex-husband and ex-wife. It was very incestuous and very funny. The joke at the lab school where my daughter went was two kids meeting in the hall and one kid says to the other ‘My father can beat up your father!’ and the other kid says, ‘Don’t be stupid, my father is your father.’”

Sally married again, this time to a lawyer. They bought a ramshackle old farm house that had once been on the outskirts of the city and was in need of repair. The marriage was quickly in jeopardy over the issue of children; she wanted more, he didn’t. Undeterred, Sally bought power tools, learned how to the fix the plumbing, and remodeled the entire house, to the chagrin of her male friends. In the middle of the city, she cultivated a garden.

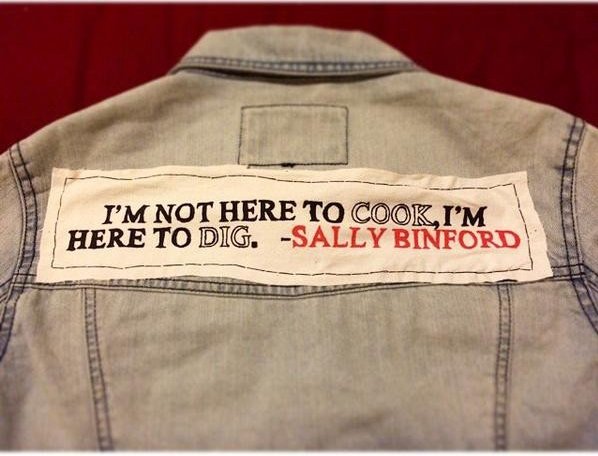

IV: I’m Not Here to Cook, I’m Here to Dig

In 1956, when Susan was in third grade, Rosen Binford enrolled as a graduate student in the Department of Anthropology at Chicago. By the age of 32, Sally had figured out that what she really wanted was autonomy, and marriage was not the answer. At the end of her first year in graduate school, after her husband became jealous of her new colleagues, they divorced.

To her dismay, at Chicago she was greeted with open misogyny from the get-go. At a tea for incoming graduate the students, the chair of the department remarked, “‘This is a professional department and we always get a few dilettante housewives and types like that in here.’” The chair’s wife leaned across the table and said to Sally, “‘Don’t you listen to a word he says, honey, you stick with it.’”

“If ever my feminist conscience was forged it was during the experience of being a grad student in the Anthro Department at the University of Chicago.” Although the most famous anthropologist in America was a woman — Margaret Mead — few departments hired female faculty members. Sally felt isolated as a woman and because of her age. But she was passionate about archaeology, and unwilling to let these obstacles get in her way. As her adviser, Rosen Binford chose F. Clark Howell, one of the fathers of paleoanthropology, who made no apologies about the hostile atmosphere. Howell was a dedicated mentor, however, and routinely went to bat for Sally. He made it clear that she was resented in the department for being a woman — for her social life and for wearing “tight sweaters and makeup,” as Howell put it. He told Sally, “I don’t think you’ll get a Ph.D. out of this department, but if you do good work, I’ll back you.”

But it turns out that Sally didn’t do good work. She did excellent work.

Chicago’s policy was to admit large numbers of students and let attrition and comprehensive exams winnow them down, resulting in only three or four PhD’s per cohort. Sally, encouraged by the fact that students were identified by number rather than by name on the exams, passed with flying colors. However, when she checked with the secretary to verify her registration to finish her PhD in the fall, Rosen Binford was told she had been given a terminal master’s degree instead — meaning no doctoral program. The secretary realized that the chair of the department had forwarded the wrong grade to the registrar. With Howell’s help, she was able to get the error corrected, but was left with the disconcerting feeling that the chair had made the “mistake” on purpose.

During the summer of 1960, Sally excavated with a team from Harvard in France. The excavation was conducted like a military campaign by Abri Pataud who, according to Rosen Binford, who “didn’t like women, didn’t like Jews, and didn’t believe in divorce” — three strikes against her from the start. The excavation director explained to Sally that at ten o’clock each morning she would go help his wife with the shopping and prepare lunch for the crew — an order that she refused. After insisting that Rosen Binford follow his directions, she replied, “I’m sorry. I’m not here to cook. I’m here to dig.” Pataud didn’t speak to her for the rest of the summer.

That summer Sally became friends with Francois Bordes and Denise de Sonneville Bordes, two of the most preeminent paleolithic archaeologists in the France during the 1960s, who lived near the University of Bordeaux in southwestern France. In the evenings, the Bordes fed Sally brandy and gave her a shoulder to cry on. Their advice was to tough it out. The two archaeologists became allies, and formed the bedrock of a friendship that weathered the fierce intellectual debates between Lewis Binford and Francois Bordes in the 1970's.

Sally returned to Chicago and completed her PhD in 1962. Her dissertation detailed the geological and archaeological history of the Sahara Desert during the Pleistocene (Ice Age). “There was a lot of nonsense written about how the black race had been separated from the white race for a long time and the Sahara had been a barrier for gene flow because it was a desert and prehistoric populations couldn’t live there and therefore blacks were very, very different from Europeans. It was essentially a racist argument.”

V. TrowelBlazer

Her next focus was the transition from Neanderthal to modern populations in France and Israel. The primary data were stone tools and animal bones, specifically correlations between different types of tools and how animals were butchered. Hunter-gathers carry tool kits, and they tend to be organized somewhat like a toolbox or a surgical set. Some tools — a pocket knife, a scalpel — are good for a wide range of tasks, and could be expected to be common in each respective tool set. Complex, specialized tools, however, might point to specific tasks or types of work. Increasingly complex types of stone tool kits reflect highly-organized hunting tasks, and in terms of human evolution, parallel the development of behaviorally modern humans.

Sally Binford’s Chapter “Ethnographic Data and Understanding the Pleistocene” appeared in one of the most well-known anthropology volumes of the late 1960s, Man the Hunter

In each of her articles written in the 1960s, what Rosen Binford saw in the assemblages of Paleolithic stone tools was not different ethnic groups, but rather differences in function: people doing different things at different locations. This may sound like a minor point, but it was in fact an extremely important precursor to later attempts by American archaeologists to use statistics and computers to make sense of stone tools and ancient human behavior. “Unless you have formulated hypotheses which can be tested, it’s just science fiction…interpretations about their ideology or their spiritual life or their ethnic loyalties — we don’t find this stuff in sites.”

In looking at the tools she also found that modern humans, in stark contrast to Neanderthals, went after a single species of herd animal (cattle in the Middle East, mammoth in Eastern and Central Europe and North America, reindeer in Western Europe) that could be predictably hunted along their seasonal migration routes and in large numbers. “These guys knew that food was coming through twice a year. They could smoke it. If it was at the height of the Ice Age in France, they could freeze it. They got tremendous time utility out of this resource. When you start getting large groups of people, assembled for a semiannual protein harvest, they develop rules about reciprocal rights between groups which are most often defined by mating patterns. This increases gene flow between and it also means a tremendous amount of cooperation is necessary between groups…It wasn’t until people started settling down, building cities, creating a class structure, having investment in corporate capital, corporately owned resources, that warfare started.”

During this time she also discovered she loved excavating: “Digging is fun — getting away from the library, ‘facking fuckulty meetings’ and academic politics and sitting in cool caves and then coming out and eating French food three times a day and getting paid for it.”

VI. Leaving Lascaux

During the summer of 1960, while Sally and Susan were excavating with the crew from Harvard in France, they were invited to visit Lascaux Cave, famous for its depictions of extinct aurochs, horses, bison, and other Ice Age creatures. The crew was informed that they were allowed to go inside at night, when the cave was closed to the public.

Sally and Susan entered the cave at about six o’clock that night. Armed with a single flashlight, they descended through a series of doors leading down into the caves. For Sally, it was a powerful, nearly psychedelic experience. Passing through the main chamber, they pointed their flashlight up to see the white calcite walls of the cave overflowing with enormous, polychrome paintings of galloping herds of animals, depicted in motion. “The place has a very, very important feeling. The artwork from the late Upper Paleolithic is exquisite. You are amazed by the level of artistry and the degree of anatomical knowledge they had. There were tremendous techniques developed by master artists that were lost and not rediscovered until the Renaissance.”

Hall of Bulls, Lascaux Cave

When they returned to the entrance later, they found that the lights were off and the door was locked from the outside. The rest of the crew had returned to the hotel. The flashlight grew dim, and they began pounding on the door and yelling for help. Terrified, Susan asked, “What are we going to do?” Sally replied, “We may be the first people in 12,000 years to spend the night here, look at it that way.”

Sally and Susan waited in the freezing, pitch black cave for three hours until the crew realized they were missing and went back to rescue them. When Susan returned to school the next fall, she wrote a “What I did on my summer vacation” essay. Her teacher was incredulous until Sally showed up at the school and explained that Susan wasn’t lying — they had in fact been trapped at night in a cave full of Ice Age art in the middle of nowhere in France the previous summer.

Lascaux was closed to the public permanently in 1963. Today, a creeping black mold thought to be the result of human activity is slowly destroying the ancient paintings, suggesting that our inquiry into our own past can in some cases be corrosive. The original cave is now open only to scientists and preservationists for a few days each month. Visitors, however, may tour a replica of it that is close by: the past as simulacrum.

VII: Binford & Binford, Les Enfants Terribles

In 1961, Sally Rosen met Lewis Binford, a maverick in the field of archaeology in the 1960’s and 1970’s, and together they would change the course of each other’s lives and shake up the field of archaeology forever. Lewis Binford had been asked to join the faculty of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Chicago as an assistant professor while still finishing up his dissertation at the University of Michigan. Lew Binford, among other things, wanted to recast archaeology in the fashion of the physical sciences and make our understanding of prehistory scientifically falsifiable. The call-to-arms for this was laid out in an article he wrote during his first year at the University of Chicago, famously entitled Archaeology as Anthropology: “Archaeologists should be among the best qualified to study and directly test hypotheses concerning the process of evolutionary change…with the entire span of culture history as our ‘laboratory,’ we cannot afford to keep our theoretical heads buried in the sand.”

Within a few short years, Lewis Binford’s tendency to push, prod, lecture, and scold other archaeologists would alienate most of the senior faculty at the University of Chicago, but in 1961, he was still considered a wunderkind. Although he was seven years younger than her, like Sally, he had been married several times. They had offices next to one another in the Department of Anthropology, where each of them was teaching, publishing, and trying to hurriedly finish up their dissertations, in addition to excavating during the summers. Sally and Lew found each other charming, and by measures became friends, and then good friends. Sometimes late at night, he would drop by her apartment in Chicago, but Sally always stuck to her rule, one that had paid off well over the course of graduate school: don’t sleep with faculty. And that was that.

In 1962, Sally won a National Science Foundation grant to excavate a Neanderthal site in Israel. The political climate under David Ben-Gurion, founder and first prime minister, was an eye-opener for her. “I went to Israel feeling I never had been pro or anti-Zionist. Being Jewish, I had a generalized sympathy toward Israel, but when I went there I was horrified by what I saw.” Her archaeological site was in a wadi, a valley that emptied into the Sea of Galilee below. Each night, Sally would sit high in the hills above the excavation and watch Syrian and Israeli artillery shells exploding like fireworks against the ocean of stars above. On some nights, you can still see this today.

When Sally returned from Israel, Lew was waiting for her, and they began their romance. “He was running a dig the summer of 1963 in Southern Illinois and I went with him to work. He was coming up for tenure. Lew was extremely smart, but extremely crazy and aggressive.” Binford was already on thin ice with the senior faculty at Chicago, and thought that living with Sally without being married would negatively affect his chances at tenure. At the end of the excavation, he proposed to her.

Sally replied, “‘Lew, marriage is not my thing. I’ve tried it twice and I’m not good at it…I will marry you for the sake of your tenure, but I’ll tell you now this is not going to be a permanent deal because I know myself well enough to know that marriage is not my thing.’” They quickly became a professional couple of some note. Their skill sets were complimentary: Lew worked in North America, while Sally worked in Europe and the Middle East; while Sally was all about the data, Lew was a theory wonk, but also good with statistics. Within a few years, the Binfords would produce half a dozen articles and two co-edited books together. “The articles were mostly on theory and ways of analyzing data that was innovative and unconventional for the time. We questioned a lot of the premises underlying most archaeological interpretations and brought some scientific rigor into the field, in terms of formulating and testing hypotheses, instead of people just looking at data and making up a story.” The Binfords did the first computer analysis of stone tool assemblages in 1966, which was considered radical for its time.

It is impossible to explain the Binfords life together without confronting some messy and unpleasant incidents in their marriage and career. It’s important to understand Lew Binford’s cult-like status in archaeology in the 1970’s, 80’s, and 90’s, which cannot be overstated; one of my PhD advisors was a Binford acolyte, and I too inherited a strange and irrational admiration for him as an archaeologist, as have many others (which certainly was not inspired by Binford’s writing, which is a crime against syntax). He inspired intense loyalty among his students, and, as archaeologist Liz M. Quinlan points out in “‘…and ‘his wife, Sally’: The Binford Legacy and Uncredited Work in Archaeology”, Rosen Binford’s role, influence, and contribution to his work have been whitewashed for many decades. To gloss over the details of their relationship is a step in the wrong direction and does a disservice to people in emotionally or physically abusive relationships. Moreover, I think when you strip away the ugly truths from a history it becomes a fantasy, and perhaps a story that isn’t worth telling — or at least not worth it for me to tell. Sally’s words speak for themselves, and I think it’s also important to frame the following in the context of a certain type of codependent marriage and bitter divorce between two really brilliant, really crazy people with some substance abuse issues.

“Lew didn’t have grad students as much as he had disciples. He was very charismatic and he turned out some real first-rate students in Chicago during the time he was there. He had been a grad student at Michigan, but he had thesis problems and couldn’t finish his Ph.D. He couldn’t pass his French exam which the University required for him to get his Ph.D.”

Sally helped Lew pass his French exam in absentia, and smoothed out his occasionally impenetrable prose. “He was an extremely brilliant guy, but couldn’t write a sentence that made sense. His writing was unspeakable. My job in the marriage became to translate what Lew wrote into English and to get him his Ph.D.” According to Rosen Binford, he would generate countless original, innovative theoretical ideas and relied on her to find data sets that supported them and make them comprehensible.

As she put it, “My role was superwoman. I could do anything. I could cook, clean house, take his exams for him, translate his thesis into English. I could do all this and still carry on my own career. The first two years we were together we were both turned-on intellectually and sexually. It was a very, very high time for us both.” Rosen Binford got a job teaching at Northwestern and commuted from the south side of Chicago. They were both workaholics who partied hard on the weekends, particularly Lew.

Although he finished his PhD, in 1965 Lewis Binford was denied tenure at the University of Chicago. The University of California Santa Barbara, looking to strengthen its anthropology program, hired Lew as an assistant professor and Sally as a lecturer. She found the adjustment to southern California a difficult one, and missed the intense intellectual atmosphere at Chicago. “I arrived with my hair back in a bun, dressed in my spike heels and knit suits. Little girls were running around in mini skirts and no bras. Everybody was stoned all the time. There were 85 kids in the first class I taught, an introductory course in human evolution. I realized about halfway through the course that one of the reasons I was having trouble in teaching those kids is that they were all stoned.” It was a total culture shock.

A few members of the department at UCSD were openly anti-Semitic, which Rosen Binford immediately bristled at. “I made a great point of signing myself Sally Rosen Binford. I also made a point of speaking a few words of Yiddish at the faculty gatherings.” There were other attitudes towards racial and ethnic minorities that created a tense atmosphere. The department was in the midst of a growth spurt, and was recruiting anthropologists with expertise in Native American and African cultures to come to Santa Barbara. Sally knew Alfonso Ortiz [a Tewa-speaking Native American scholar and activist], a William Shack [a distinguished Africanist who had a long career at Berkeley], and recommended them for the positions. After the faculty meeting, the chair of the department reportedly remarked, “‘Doesn’t she know any white people?’”

Afterwards, Sally told Lew that she couldn’t work another year in such a repressive and discriminatory atmosphere. “The library is terrible, and the chairman is a fucking racist.” When the Binfords contacted UCLA to see if they could have their contract transferred, the faculty there were thrilled. And so off they went to Los Angeles.

VIII: La La Land

When they arrived, the Binfords rented a house in the hills overlooking L.A. where they gathered their friends and cooked elaborate meals. By the end of the 1960s, Binford & Binford had reached the peak of their productivity as a power couple in archaeology, publishing papers and books, chairing symposia at national meetings, running excavations, and spreading the good word of the New Archaeology. In many ways, 1968 was Rosen Binford’s annus mirabilis. She was awarded another NSF grant, was the lead author on two co-edited books (Archaeology in Cultural Systems and New Perspectives in Archaeology), and published four single-authored articles and chapters (Early Upper Pleistocene Adaptations in the Levant, A Structural Comparison of Disposal of the Dead in the Mousterian and the Upper Paleolithic, Variability and Change in the Near Eastern Mousterian of Levallois Facies, and Ethnographic Data and Understanding the Pleistocene). This is an extraordinary amount of scholarly work in one year, particularly considering that she was a wife, a mother, and a teacher in addition to being an archaeologist. 1968 turned out to be not only the zenith of her academic career, but also the beginning of the end. Despite her professional success, Sally was pissed off about Lew’s drinking, about the rampant sexism and racism in the discipline, and with the infiltration of the CIA into anthropology departments across the country.

“During the early Sixties, when the big boys in Washington decided the Third World was where the action was, a lot of funny grad students started turning up in anthropology…what better cover could anybody have than being an anthropologist. When a friend of mine who had done field work in East Africa came back, she was debriefed by the CIA about what was happening there. She said nothing was happening in Africa in the last 100,000 years that was of the slightest concern to her. Another friend of mine who had done field work in Iran was told to turn over her field notes to [the CIA] and when she didn’t was told that she would just never get any more grant money. It’s not just paranoia on my part, believe me. I was becoming disenchanted very rapidly.”

As at Santa Barbara, at UCLA Lew was given the tenure track position and Sally was again given the subordinate job of lecturer, despite her crucial role in their work. At this point in the late 1960s, anthropology programs were growing rapidly, and they were both offered full-time positions at the University of New Mexico — a potential solution this dilemma. “It sounded tempting, but at that time the marriage was in very bad shape. I knew in 1967 that the marriage was through, but Lew’s and my lives were so connected in the field that it wasn’t going to be easy to get out.”

Rosen Binford wanted to break away from her work with Lew, and follow her own interests. In 1968 she won a National Science Foundation senior postdoctoral grant to do research the following year on Neanderthal sites in Israel. When she told him, Lew replied “‘If you go, I won’t be here when you get back.’” Although she felt as if she had put her own career on hold for him, eventually she capitulated, and they applied for a different grant, something Sally saw as a huge mistake in hindsight.

“It was probably one of the weirdest and most awful years of my life. I was so furious with him and so resentful. He was drinking and became physically abusive. In 1966 or 1967 at UCLA we were having a fight about something. I said something very sarcastic and he took his hand and just cracked it across my face and sent my glasses flying across the room. He was 6’3” and over 200 pounds.” The police were not anxious to help, and more or less did nothing. Sally was, understandably, furious. “A few days later I said, ‘You are so helpless, you can’t even boil water. I cook everything you eat and everything you drink. I just want to tell you the next time you lay a finger on me you are going to wonder what the hell is in that cup of coffee, that bowl of soup.’”

“We left Los Angeles and went to France for a hideous year — the year was dreadful, in terms of work, in terms of politics, our relationship. We came back to Albuquerque, which has to be the ass-end of nowhere. I said okay, I signed a contract; I’ll teach my classes this year but when this year is over I’m leaving…but the more I withdrew from him, the crazier and more violent he got. He was hospitalized a couple of times because he was hallucinating.” When Lewis Binford went to Alaska to do fieldwork in the spring of 1969, Sally did what any sane person would do: she packed up her things, put the dog in the car, and left him forever.

IX: A Bigger Marriage

Like a lot of people whose lives come unraveled during the process of graduate school and divorce, Rosen Binford was disenchanted with academia but felt so tangled up in her field that she couldn’t simply abandon her career. “I was really in a weird position where the subject matter still turned me on, but I thought…I just cannot sit through one more faculty meeting with these bastards. I’m going to stand up and scream, ‘You’re just a bunch of sexist, racist, right-wing pigs!’ Of course, at this point I had a reputation as a troublemaker in the field. Being a smart, uppity woman did not win me any favors.” Although she was offered a job at the University of Montana, Sally decided to head back to the west coast, get a place on the beach, and figure out what the hell she wanted to do with her life.

When her father died in 1968, Rosen Binford had inherited a small sum money, enough to get a modest apartment and some much-needed breathing space after the acrimonious end of her relationship with Lew. She moved back to L.A. and settled in Venice, where she spent a lot of time walking on the beach with her dog, mulling over the tumultuous past decade spent in academia and wondering what direction to move in next. It was in California that Sally began to experiment with LSD, mescaline, and other psychedelics for the first time.

She received a call from Ed Brecher, an old friend from New York who was a pioneering sex education researcher and author of several well-known books such as The Sex Researchers and Love, Sex, and Aging. Their intellectual interests were similar: both were involved in the right-to-die movement, and promoting sex education and sexual liberation (in 1974 Ed and Sally would costar in a short, sexually explicit film entitled “A Ripple in Time” that explored the sex lives of the elderly, a sort of first of its kind). During the call, he told Sally about Sandstone, a clothing-optional, open-sexuality commune located on a fifteen acre ranch in Topanga Canyon, at the time home to Joni Mitchell, Crosby, Stills, and Nash, Jim Morrison, Frank Zappa, and other cultural luminaries. Brecher, stoking her anthropological curiosity, urged Rosen Binford to go and see what was happening at Sandstone and report back.

What Sally found high in the hills above Malibu fascinated her. “There were seven people living there full-time, in what was essentially a group marriage. They were all middle-class drop-outs who had done a little Fritz Perls [psychotherapy], a little psychedelics, and had decided their lives were shit and there must be something a little better than what they were doing. They were experimenting with open sexuality and trying to find ways of forming relationships that were meaningful.”

‘The Sandstone Foundation for Community Systems Research’ was a utopian community founded by John and Barbara Williamson and famously portrayed in Gay Talese’s 1980 book on the American sexual liberation movement, Thy Neighbors Wife: A Chronicle of American Permissiveness Before the Age of AIDS. At its height, Sandstone attracted a wide range of cultural figures, including biologist Alex Comfort (author of The Joy of Sex), actor and NFL star Bernie Casie, and the pornographer Marvin Miller, for whom the Supreme Court’s obscenity test (the Miller Test) is named.

John Williamson, an engineer for Lockheed, and his wife Barbara Cramer, an insurance executive, met at a sales meeting in southern California in 1966. Five weeks later they married in Las Vegas — a marriage that lasted nearly half a century, until John’s death in 2013. The particular alchemy between the Williamsons that caused them to leave behind their white-collar lives to start an open sexuality commune is perhaps unknowable, but according to Barbara, the couple quickly recognized that, “a traditional heterosexual marriage could not last, because two people could not give each other everything they need. So we built a bigger marriage.” Their goal was to understand society, and in the process set it free — goals that Binford identified with and found attractive after leaving her academic life behind. In the summer of 1970, Sally officially joined Sandstone, and spent the better part of the next two years there.

Sandstone initially supported itself by taking on members: weekdays were filled with sunbathing and swimming, and weekends with bacchanalian revelries among a self-selected group of sixty or seventy people. Sally kept her own apartment down on the beach in Malibu, but went to Sandstone on the weekends and for parties. “There were nights there when I would put on my anthropologist’s hat and just sit back and watch the primates behave.”

Drugs were officially forbidden on the premises; the Williamsons shrewdly understood that the quickest end to their social experiment would be a drug bust. However, the use of psychedelic drugs was common, if somewhat covert — that is, as covert as a large group of tripping, naked hippies can be. Nudity and open sex were optional, but consent was not: “If you approached somebody and they said no, the answer was NO period.”

The Sandstone compound had no doors, and thus everything that happened — whether it was sex or an intimate conversation or a trip to the bathroom — happened publicly, which served to function as what anthropologists refer to as a social “leveling mechanism”, promoting an air of honesty and egalitarianism. You often had no idea if the person you were talking to was a writer, a lawyer, a construction worker, an anthropologist, or a drug dealer.

At Sandstone, Sally formed some of the closest friendships she would have for the rest of her life. She become part of a close-knit group of twelve to fifteen people, some of whom were married and some of whom were not. “We had sex together; we did acid together; we howled at the moon together and we became really tight friends.”

An entire chapter of Talese’s book The Neighbors Wife is devoted to Sally. In the book, her accomplishments and ideas are downplayed in favor of descriptions about her divorces and sexual partners. Rosen Binford’s entire academic career is summarized as thus: “She spent the first two decades of her life in New York, where she was born and reared, and the next two decades in Chicago, where she acquired four college degrees and three husbands.” When he does give her credit for her accomplishments, it’s typically undercut by something salacious. Consider, “She was a decade ahead of the feminist movement in America; and yet, right as she was, she had a facility for falling in love with the very men who made the least compatible husbands — male chauvinists like her father. As a consequence, her marriages were contentious and temporary; and Sally, often alone and restless, unable to satisfy her amorous desires, spent many solitary evens in bed masturbating.” When Talese describes Sally’s passions, they are “orgies” and “orgasmic jubilation” and not anthropology and political activism. What’s clear from a close reading of Thy Neighbors Wife is that in the course of his research, Gay Talese didn’t read a word of her scientific work.

X. The Feds

In 1970, Rosen Binford was introduced to a former employee of the RAND Corporation named Tony Russo who had grown disenchanted with its involvement in the Vietnam War and recently become an ardent anti-war activist. Tony introduced Sally to Dan, who also worked for RAND, and she subsequently invited them to Sandstone, where they both became regulars on the scene. Tony and Dan had frequent, secretive conversations, and when pressed as to what they were conspiring about, would only go so far as to cryptically respond, “Don’t ask. It’s better if you don’t know.” Maybe it was just the acid talking, she thought, or maybe they were just off their rockers. Sally noticed the trunk of Dan’s car was filled with official government documents. Tony was consumed with paranoia, often saying that his phone was being tapped or that he was being watched. But at the time, just months after the Manson Murders, the atmosphere of southern California was tense, rife with drug-fueled paranoia, and so this was not an uncommon feeling.

But as it turns out, it wasn’t just the acid talking.

What Rosen Binford didn’t know was that a few months earlier, in October of 1969, Dan (who was Daniel Ellsberg) and Tony (who was Anthony Russo) had secretly made photocopies of the classified documents known as the Pentagon Papers while working at RAND. They then leaked all 43 volumes to Neil Sheehan of the New York Times. The Pentagon Papers clearly illustrated that the Vietnam War was, in the estimation of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, completely unwinnable — but also that President Lyndon Johnson had systematically lied to both Congress and the public about it.

However, the gravity of Dan and Tony’s involvement in the leaking of the Pentagon Papers — one of the test cases in the moral history of the United States — would not be known to Sally or the other members of Sandstone until June of 1971. She first heard about the release of the documents on the radio while driving up the Pacific Coast Highway to a party at Sandstone. Whoever had leaked them had to be someone that worked for both the Department of Defense and for RAND. The only person that she could think of that fit this description was Ellsberg.

Her initial shock was confirmed when the FBI arrived at Sandstone in the summer of 1971 and began to ask questions. According to Sally, after FBI informants were sent to join Sandstone the community fell apart very rapidly. She was contacted by Ellsberg’s lawyers, who told her that Dan would only talk to her on a pay phone. It was bizarre, but she was doing enough LSD at the time to make her suspect that she was just being paranoid. When Rosen Binford called him, they agreed to meet at a busy Jewish deli in Santa Monica where the noise would prevent anyone from overhearing their conversation. While anxiously looking over his shoulder, Ellsberg told her that Richard Nixon and John Mitchell (the Attorney General) were convinced the release of the Pentagon Papers was a vast left-wing conspiracy, and were determined to put him behind bars.

Afterwards, Sally was contacted by the FBI about Ellsberg but refused to answer any questions. She claimed to have been followed by mysterious men in trench coats and suspected her phone was tapped. A month after seeing Ellsberg off at the airport in L.A., two FBI agents showed up at her front door with a subpoena to testify before a grand jury. After consulting her lawyer, Rosen Binford refused to testify, citing her First and Fourth Amendment rights. She avoided jail, but found the entire ordeal to be a terrifying, life-changing experience. She worried about the FBI searching her or her daughter’s house (Susan lived with her son Tim close by) for drugs in order to incriminate her, but her lawyer told her not to bother. “If [the FBI] wants to find drugs in the house, they’ll just plant them there.” A year later, she was glued to the television watching the Watergate hearings and waiting to hear about the outcome of Ellsberg’s (who could have served a maximum of 115 years if convicted) case, which the judge dismissed because of government misconduct.

XI: The Endless Road Trip

Rosen Binford and Jeremy Slate

Rosen Binford’s disenchantment with Sandstone grew quickly following FBI surveillance and the paranoia it brought about, and a massive outbreak of venereal disease. Sally had formed a close relationship with the actor Jeremy Slate (best known for his roles in soap operas like One Life to Live and Guiding Light), whom she would remain close to for the rest of her life. When they were both infected by the outbreak at Sandstone, they decided it was time to leave for good. Sally and Jeremy moved to the Mill Valley area north of San Francisco, and Jeremy occasionally traveled back and forth to Hollywood to do part-time acting in order to pay the rent.

In the spring of 1972, Sally was invited to teach several courses in anthropology and Women’s Studies courses at Goddard College in Plainfield, Vermont. While Godard seemed like an idyllic refuge from a distance, it was unrelentingly cold from November until May, especially for two people accustomed to southern California. After being a practicing nudist for two years, it was hard for Sally to adjust to donning long underwear, sweaters, gloves, boots, scarves, coats, and a hat before stepping out the door.

During this time, the scope of her writing broadens, and she begins to connect her anthropological and activist interests. In an article from 1972 entitled “Apes and Original Sin” she writes, “Man, alas is one of the most savage of beasts. He plunders, rapes and kills, and worse yet, articulates high sounding reasons for all of this nastiness. Where did we go wrong?” This essay is a direct response to many pop science books that at that time proclaimed the violent nature of human ancestors, which some used to explain (and occasionally justify) modern forms of violence as genetic. “We are not doomed to act out a drama whose lines were written millions of years ago. Culture is cumulative; humans can and do learn more about their environment and themselves…Complex truths often fail to catch up with the simple attractive lie.”

It didn’t take Rosen Binford long to realize that she disliked Goddard for the same reasons she disliked Vassar: it wasn’t intellectually serious enough for her. She viewed it as a place that upper middle-class parents sent their druggy kids to when they couldn’t get into the Ivy League. In 1973, Sally and Jeremy put everything they owned in storage, bought a motorhome, and left Goddard for the West Coast. They spent three years crisscrossing the country, visiting friends, and travelling around Mexico, intermittently returning to L.A. when they ran out of money so that Slate could take part-time acting work. It was a lifestyle they both loved.

In 1976, they had a custom motor home built to travel around Hawaii, where they continued their endless road trip adventure. Sally loved taking mushrooms and going snorkeling to examine the aquatic underworld — “just going crazy,” in her words. In 1978, they finally returned to San Francisco. Slate and Rosen Binford, both bisexual, had an open relationship, and often invited friends to sleep with them. For a while, this worked. “We loved to bring home a friend and play; that was our thing. When we got to San Francisco it became very clear to me here that the most interesting people in this town were gay. I started hanging out with a neat bunch of dykes I knew, and Jeremy started hanging out in the gay baths.” Rosen Binford fell in love with a woman named Jan, who was 20 years her junior. Jeremy, threated by the intensity of their connection, decided to move on. The endless road trip had finally come to an end.

Sally and Jan stayed together for the next seven years. Sally was fascinated with the lesbian scene in the Bay area: “I had my anthropologist hat on the whole time thinking — my god, I really should be doing a paper on this whole subculture.” Sally, however, began to feel her age, and both of them grew sexually restless in a monogamous relationship. While Sally could have sexual relationships with friends and acquaintances for fun, Jan eschewed casual sex, and needed to be in love with her sexual partners. Eventually, Jan fell in love with a younger woman. Sally, who had always assumed that jealousy was a social construct, was shocked when she soon felt like she was being eaten alive it.

To repair the rift, the two decided to return to Hawaii. “We lived in Haiku near the pineapple fields in a funny little place called “Rice Camp”, which was a settlement of Hawaiian and Filipino pineapple workers. We were the only ‘haoles’ there, certainly the only female couple there.” In was in Maui where Rosen Binford started to become engaged in activism again again, serving as an organizer for gay rights groups and running workshops on sexuality and aging. Her relationship with Jan, however, began slip away when Jan returned to San Francisco, leaving Sally alone in Hawaii. When she returned to California, Jan had again fallen for someone else.

XII: “Every group invents a mythical past when they were once powerful and strong.”

In 1979, Rosen Binford wrote an article entitled“Are Goddesses and Matriarchies Merely Figments of Feminist Imagination? Myths and Matriarchies”, a counterargument directed against the Mother Goddess movement of the 1970s and 1980s. The Goddess hypothesis held that deep in antiquity, prehistoric groups were matriarchal, peaceful and egalitarian, and lead by women who worshiped earth goddesses. The mother of the Mother Goddess movement was undoubtedly Marija Gimbutas, a Harvard archaeologist who promoted her matriarch-centered prehistory in popular books such The Language of the Goddess or The Civilization of the Goddess which sold millions of copies, and which had been preceded by similar Goddess-movement books such as Merlin Stone’s When God Was a Woman (1976). These ideas of women in prehistory as peaceful stewards of the earth tapped straight into the zeitgeist, serving as both a unifying force for feminists in the 1970s and 80s, and as a critique of a misogynist, patriarchal culture that was bringing humanity to the brink of nuclear war and environmental collapse.

Rosen Binford, along with other archaeologists, challenged this interpretation and asserted that there was very little hard evidence of a pervasive Goddess Culture in prehistoric Europe and the Old World. In “Myths and Matriarchies” she writes, “One of the basic objections to the mythic matriarchal past — apart from the lack of evidence to support it and the consistent body of data that argues against it — is the use of myth as history by the propagators of the faith. We do not attempt to reconstruct biological evolution or the history of the universe by recourse to myth…Myths are not appropriate data for reconstructing the past.” This drew heavy criticism from some feminists, who declared Sally’s article treasonous in its questioning of the Mother Goddess and accused her of being brain-washed by the male establishment. Binford first submitted the article to Ms. Magazine, then edited by Gloria Steinem, where it was rejected. “[Steinem] really didn’t care whether or not this matriarchy thing was true; she found it a useful thing for women to believe in. Like the tooth fairy, I guess. That struck me as being one of most patronizing, objectionable, stupid things I’d ever heard in my life.”

“I pissed off a lot of the soft-headed feminists…For them to have wasted their time on this instead of equal pay for equal work is trivializing feminism and a total waste of time. I got hate mail…The focus on the former glories of the ‘Matriarchy’ drains off a tremendous amount of energy and interest away from current problems, like reproductive rights, equal wages for equal work, medical care and so forth. Every group invents a mythical past when they were once powerful and strong.” Binford’s article eventually did get published and directly influenced other archaeologists, particularly in Cynthia Eller’s The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory: Why An Invented Past Will Not Give Women a Future.

XIII. “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world” — Margaret Mead

In her own estimation, Rosen Binford had three organizing principles in her life: politics, food and sex — “and not necessarily in that order.” Since her time at the University of Chicago, she had been an activist promoting civil rights and nonviolence. In the early 1960s, she felt that the Civil Rights Movement was something she had to be part of, and was at the Third Selma March in Alabama led by Martin Luther King in March of 1965: “We marched down the main street of Selma and there was just absolute total silence. The streets were lined with local rednecks. There were thousands of us and all that could be heard were the sound of our footfalls. It was absolutely terrifying.” She campaigned for Democratic candidates in the Chicago wards, and protested against the war in Vietnam, using her academic influence to shield students from the draft: “I helped lots of students get out of the country by calling academic connections in Canada and getting them into school there. I said I will not flunk any male student…Academia was so corrupt at that point anyhow.” During this time, Rosen Binford also became a charter member of the National Organization for Women (NOW), which is now the largest feminist group in the United States, with over a half a million members.

In the early 1980s, Rosen Binford served on the board of directors of the the Gray Panthers, a multi-generational advocacy network named in honor of the Black Panthers. The Gray Panthers challenged ageist laws and discrimination, and championed the rights of people in nursing homes and LGBTQ individuals, anti-war activism, environmentalism, intergenerational housing, and healthcare and Social Security rights. Rosen Binford was attracted to the Gray Panthers because, as she put it, “They struck me as being a bunch of old feisty people and I was coming to terms with getting old and wanted to find some way of combining politics with that. The Gray Panthers seemed to be the answer.” Binford also joined the board of Community United Against Violence (CUAV), an organization founded in 1979 following the assassination of Harvey Milk, the first openly gay elected official in the history of California. The CUAV is the oldest LGBTQ anti-violence organization in the US, and works to promote community safety in San Francisco, educational outreach, and support victims of domestic violence and hate crimes. “I keep saying I can’t go to one more demonstration, but still when political issues come up I find myself out in the street carrying a placard and marching.”

XIV. Harold and Maude

Sally’s final years were spent in San Francisco, a city that she had been drawn to since she was a child. She loved the rolling hills, the climate, the people, the ambiance, and simply walking down the street. A self-described “total food freak,” she spent immense amounts of time shopping in local markets and cooking elaborate monthly meals for herself and for her large group of friends (one of her specialties was French fries cooked in goose fat), people whom she loved and who supported her in her final years. Her poker parties and Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners were legendary.

In her mid-fifties, her body began to fail her. Until this point, Sally ate whatever she wanted, smoked and drank what she wanted, and took the drugs that she wanted to take. It never occurred to her to exercise. Soon she started having severe problems with her back and neck, and consulted orthopedic doctors, massage therapists, acupuncturists, and faith healers. Facing a spinal fusion that would be both painful and potentially ineffective, Sally decided to do the unthinkable. She decided to join a gym.

Dragged “screaming and kicking” by her then partner, after three sessions at the gym she found that the backaches she had lived with for years suddenly vanished. Her newfound love of exercise surprised her: “If anyone had told me fifteen years back that I would be a geriatric gym junkie, I would have just laughed.”

The invisibility that so many elderly people feel was a type of freedom for her, providing her with perspective. Used to being whistled and catcalled at in her younger years, she felt she was no longer a target of sexual harassment, and the invisibility of her 50s and 60s allowed her to make anthropological observations more freely: “All it takes is white hair and wrinkles and to most people you are just invisible.”

As a trailblazer of sexual liberation and sex-positive feminism, her love for different types of sexual experiences didn’t diminish in her final years. Towards the end of her life, she entered, as she put it, her Harold and Maude period: “I’m seeing a 38 year old man and a 23 year old dyke. Also occasional group sex parties, safe sex, of course, with old friends.” I think Sally’s frankness about her sexuality was part of the message — not just to make our sexualities okay or even socially acceptable, but more purely to encourage us to be proud of them. She continued to volunteer as a sex educator on the San Francisco Sex Information Switchboard, fielding questions ranging from the symptoms of STDs to the best leather bars in the Castro, and as the local expert on elderly sexuality. Her motto? “Use it or lose it.”

XV. “Toujours soixante-neuf!”

Sally Binford (center), her partner Jan, and her beloved poodle Jake. Photo taken by Honey Lee Cottrell circa 1980.

Sally’s story of life after academia is not the exception but rather the rule: the U.S. pumps out roughly 184,000 PhDs per year (a number that is continually increasing) and there are over 4.5 million PhDs in the US — far, far beyond the number of permanent, tenure track teaching positions available. Chances are, if you have a PhD and are reading this, you’ve already started to figure out what life after graduate school entails. I don’t know about you, but spending most of my life training to do a very specific job and then finding myself a divorced parent with a mortgage, completely disenchanted with the career in anthropology I had chosen, was a rude awakening. Sally’s story makes me feel less alone, which, as writer David Foster Wallace once said, is ultimately the reason why we tell stories in the first place. They make us feel less alone.

Her story is also a cautionary tale about people, particularly women, who have been ghosted out of scholarly recognition and credit by their partner for professional benefit. And it presents a conundrum that a lot of my fellow anthropologists have had to face: how do you maintain scholarly objectivity while fighting for the things that made you want to enter the discipline in the first place? This is another place where Sally Rosen Binford can serve as a model for us. As archaeologist Liz M. Quinlan put it, “She was a queer Jewish woman who pursued an academic subjects traditionally dominated by men, in often anti-Semitic, homophobic, and sexist environments, and through it all she maintained her innate desire to fight for justice and equity.”

The last thing Sally Rosen Binford wrote reads:

“To those I love —

Most of you know that for some time I’ve been planning to check out — not out of despair or depression, but a desire to end things well. I’ve been lucky enough to have had a remarkable life, immeasurably enriched by the love and support of a large (if improbable) group of friends and lovers. I don’t want to let it fizzle out in years of debility and dependency. I’ve gambled enough to know that quitting while you’re ahead (or at least even) is wise.

And those of you familiar with my birthday will recognize that the timing of my exit allows me to claim as my epitaph:

Toujours soixante-neuf!

Love and good-bye,

Sally”

Her last words echo the suicide note of the most famous archaeologist of the first half of the 20th century, V. Gordon Childe, who in 1957 wrote, “Life ends best when one is happy and strong.” It is perhaps impossible to know if this influenced her decision or not. But to consider Sally’s suicide a tragedy is not only a mistake, it runs counter to her message: that death is a part of living, and that we should take seriously the possibility that a well-considered life includes a well-considered end.